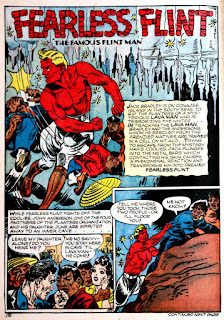

art by Harry G. Peter - Famous Funnies #92 - Eastern Color, March 1942.

Monday 30 September 2019

Saturday 28 September 2019

Good Readings: "The Ugly Duckling" by Hans C. Andersen (translated into English by Mrs. Henry H. B. Paull)

It was lovely summer weather in the country, and

the golden corn, the green oats, and the haystacks piled up in the meadows

looked beautiful. The stork walking about on his long red legs chattered in the

Egyptian language, which he had learnt from his mother. The corn-fields and

meadows were surrounded by large forests, in the midst of which were deep

pools. It was, indeed, delightful to walk about in the country. In a sunny spot

stood a pleasant old farm-house close by a deep river, and from the house down

to the water side grew great burdock leaves, so high, that under the tallest of

them a little child could stand upright. The spot was as wild as the centre of

a thick wood. In this snug retreat sat a duck on her nest, watching for her

young brood to hatch; she was beginning to get tired of her task, for the

little ones were a long time coming out of their shells, and she seldom had any

visitors. The other ducks liked much better to swim about in the river than to

climb the slippery banks, and sit under a burdock leaf, to have a gossip with

her. At length one shell cracked, and then another, and from each egg came a

living creature that lifted its head and cried, “Peep, peep.” “Quack, quack,”

said the mother, and then they all quacked as well as they could, and looked

about them on every side at the large green leaves. Their mother allowed them

to look as much as they liked, because green is good for the eyes. “How large

the world is,” said the young ducks, when they found how much more room they

now had than while they were inside the egg-shell. “Do you imagine this is the

whole world?” asked the mother; “Wait till you have seen the garden; it

stretches far beyond that to the parson’s field, but I have never ventured to

such a distance. Are you all out?” she continued, rising; “No, I declare, the

largest egg lies there still. I wonder how long this is to last, I am quite

tired of it;” and she seated herself again on the nest.

“Well, how are

you getting on?” asked an old duck, who paid her a visit.

“One egg is not

hatched yet,” said the duck, “it will not break. But just look at all the

others, are they not the prettiest little ducklings you ever saw? They are the

image of their father, who is so unkind, he never comes to see.”

“Let me see the egg

that will not break,” said the duck; “I have no doubt it is a turkey’s egg. I

was persuaded to hatch some once, and after all my care and trouble with the

young ones, they were afraid of the water. I quacked and clucked, but all to no

purpose. I could not get them to venture in. Let me look at the egg. Yes, that

is a turkey’s egg; take my advice, leave it where it is and teach the other

children to swim.”

“I think I will sit on it a little while longer,”

said the duck; “as I have sat so long already, a few days will be nothing.”

“Please

yourself,” said the old duck, and she went away.

At last the large

egg broke, and a young one crept forth crying, “Peep, peep.” It was very large

and ugly. The duck stared at it and exclaimed, “It is very large and not at all

like the others. I wonder if it really is a turkey. We shall soon find it out,

however when we go to the water. It must go in, if I have to push it myself.”

On the next day

the weather was delightful, and the sun shone brightly on the green burdock

leaves, so the mother duck took her young brood down to the water, and jumped

in with a splash. “Quack, quack,” cried she, and one after another the little

ducklings jumped in. The water closed over their heads, but they came up again

in an instant, and swam about quite prettily with their legs paddling under

them as easily as possible, and the ugly duckling was also in the water

swimming with them.

“Oh,” said the

mother, “that is not a turkey; how well he uses his legs, and how upright he

holds himself! He is my own child, and he is not so very ugly after all if you

look at him properly. Quack, quack! come with me now, I will take you into

grand society, and introduce you to the farmyard, but you must keep close to me

or you may be trodden upon; and, above all, beware of the cat.”

When they reached

the farmyard, there was a great disturbance, two families were fighting for an

eel’s head, which, after all, was carried off by the cat. “See, children, that

is the way of the world,” said the mother duck, whetting her beak, for she

would have liked the eel’s head herself. “Come, now, use your legs, and let me

see how well you can behave. You must bow your heads prettily to that old duck

yonder; she is the highest born of them all, and has Spanish blood, therefore,

she is well off. Don’t you see she has a red flag tied to her leg, which is

something very grand, and a great honor for a duck; it shows that every one is

anxious not to lose her, as she can be recognized both by man and beast. Come,

now, don’t turn your toes, a well-bred duckling spreads his feet wide apart,

just like his father and mother, in this way; now bend your neck, and say

‘quack.’”

The ducklings did

as they were bid, but the other duck stared, and said, “Look, here comes

another brood, as if there were not enough of us already! and what a queer

looking object one of them is; we don’t want him here,” and then one flew out

and bit him in the neck.

“Let him alone,”

said the mother; “he is not doing any harm.”

“Yes, but he is

so big and ugly,” said the spiteful duck “and therefore he must be turned out.”

“The others are

very pretty children,” said the old duck, with the rag on her leg, “all but

that one; I wish his mother could improve him a little.”

“That is

impossible, your grace,” replied the mother; “he is not pretty; but he has a

very good disposition, and swims as well or even better than the others. I

think he will grow up pretty, and perhaps be smaller; he has remained too long

in the egg, and therefore his figure is not properly formed;” and then she

stroked his neck and smoothed the feathers, saying, “It is a drake, and

therefore not of so much consequence. I think he will grow up strong, and able

to take care of himself.”

“The other

ducklings are graceful enough,” said the old duck. “Now make yourself at home,

and if you can find an eel’s head, you can bring it to me.”

And so they made

themselves comfortable; but the poor duckling, who had crept out of his shell

last of all, and looked so ugly, was bitten and pushed and made fun of, not

only by the ducks, but by all the poultry. “He is too big,” they all said, and

the turkey cock, who had been born into the world with spurs, and fancied

himself really an emperor, puffed himself out like a vessel in full sail, and

flew at the duckling, and became quite red in the head with passion, so that

the poor little thing did not know where to go, and was quite miserable because

he was so ugly and laughed at by the whole farmyard. So it went on from day to

day till it got worse and worse. The poor duckling was driven about by every

one; even his brothers and sisters were unkind to him, and would say, “Ah, you

ugly creature, I wish the cat would get you,” and his mother said she wished he

had never been born. The ducks pecked him, the chickens beat him, and the girl

who fed the poultry kicked him with her feet. So at last he ran away,

frightening the little birds in the hedge as he flew over the palings.

“They are afraid

of me because I am ugly,” he said. So he closed his eyes, and flew still

farther, until he came out on a large moor, inhabited by wild ducks. Here he

remained the whole night, feeling very tired and sorrowful.

In the morning,

when the wild ducks rose in the air, they stared at their new comrade. “What

sort of a duck are you?” they all said, coming round him.

He bowed to them,

and was as polite as he could be, but he did not reply to their question. “You

are exceedingly ugly,” said the wild ducks, “but that will not matter if you do

not want to marry one of our family.”

Poor thing! he

had no thoughts of marriage; all he wanted was permission to lie among the

rushes, and drink some of the water on the moor. After he had been on the moor

two days, there came two wild geese, or rather goslings, for they had not been

out of the egg long, and were very saucy. “Listen, friend,” said one of them to

the duckling, “you are so ugly, that we like you very well. Will you go with

us, and become a bird of passage? Not far from here is another moor, in which

there are some pretty wild geese, all unmarried. It is a chance for you to get

a wife; you may be lucky, ugly as you are.”

“Pop, pop,”

sounded in the air, and the two wild geese fell dead among the rushes, and the

water was tinged with blood. “Pop, pop,” echoed far and wide in the distance,

and whole flocks of wild geese rose up from the rushes. The sound continued

from every direction, for the sportsmen surrounded the moor, and some were even

seated on branches of trees, overlooking the rushes. The blue smoke from the

guns rose like clouds over the dark trees, and as it floated away across the

water, a number of sporting dogs bounded in among the rushes, which bent

beneath them wherever they went. How they terrified the poor duckling! He

turned away his head to hide it under his wing, and at the same moment a large

terrible dog passed quite near him. His jaws were open, his tongue hung from

his mouth, and his eyes glared fearfully. He thrust his nose close to the duckling,

showing his sharp teeth, and then, “splash, splash,” he went into the water

without touching him, “Oh,” sighed the duckling, “how thankful I am for being

so ugly; even a dog will not bite me.” And so he lay quite still, while the

shot rattled through the rushes, and gun after gun was fired over him. It was

late in the day before all became quiet, but even then the poor young thing did

not dare to move. He waited quietly for several hours, and then, after looking

carefully around him, hastened away from the moor as fast as he could. He ran

over field and meadow till a storm arose, and he could hardly struggle against

it. Towards evening, he reached a poor little cottage that seemed ready to

fall, and only remained standing because it could not decide on which side to

fall first. The storm continued so violent, that the duckling could go no

farther; he sat down by the cottage, and then he noticed that the door was not

quite closed in consequence of one of the hinges having given way. There was therefore

a narrow opening near the bottom large enough for him to slip through, which he

did very quietly, and got a shelter for the night. A woman, a tom cat, and a

hen lived in this cottage. The tom cat, whom the mistress called, “My little

son,” was a great favorite; he could raise his back, and purr, and could even

throw out sparks from his fur if it were stroked the wrong way. The hen had

very short legs, so she was called “Chickie short legs.” She laid good eggs,

and her mistress loved her as if she had been her own child. In the morning,

the strange visitor was discovered, and the tom cat began to purr, and the hen

to cluck.

“What is that

noise about?” said the old woman, looking round the room, but her sight was not

very good; therefore, when she saw the duckling she thought it must be a fat

duck, that had strayed from home. “Oh what a prize!” she exclaimed, “I hope it

is not a drake, for then I shall have some duck’s eggs. I must wait and see.”

So the duckling was allowed to remain on trial for three weeks, but there were

no eggs. Now the tom cat was the master of the house, and the hen was mistress,

and they always said, “We and the world,” for they believed themselves to be

half the world, and the better half too. The duckling thought that others might

hold a different opinion on the subject, but the hen would not listen to such

doubts. “Can you lay eggs?” she asked. “No.” “Then have the goodness to hold

your tongue.” “Can you raise your back, or purr, or throw out sparks?” said the

tom cat. “No.” “Then you have no right to express an opinion when sensible

people are speaking.” So the duckling sat in a corner, feeling very low

spirited, till the sunshine and the fresh air came into the room through the

open door, and then he began to feel such a great longing for a swim on the

water, that he could not help telling the hen.

“What an absurd

idea,” said the hen. “You have nothing else to do, therefore you have foolish

fancies. If you could purr or lay eggs, they would pass away.”

“But it is so

delightful to swim about on the water,” said the duckling, “and so refreshing

to feel it close over your head, while you dive down to the bottom.”

“Delightful,

indeed!” said the hen, “why you must be crazy! Ask the cat, he is the cleverest

animal I know, ask him how he would like to swim about on the water, or to dive

under it, for I will not speak of my own opinion; ask our mistress, the old

woman—there is no one in the world more clever than she is. Do you think she

would like to swim, or to let the water close over her head?”

“You don’t

understand me,” said the duckling.

“We don’t

understand you? Who can understand you, I wonder? Do you consider yourself more

clever than the cat, or the old woman? I will say nothing of myself. Don’t

imagine such nonsense, child, and thank your good fortune that you have been

received here. Are you not in a warm room, and in society from which you may

learn something. But you are a chatterer, and your company is not very

agreeable. Believe me, I speak only for your own good. I may tell you

unpleasant truths, but that is a proof of my friendship. I advise you,

therefore, to lay eggs, and learn to purr as quickly as possible.”

“I believe I must

go out into the world again,” said the duckling.

“Yes, do,” said

the hen. So the duckling left the cottage, and soon found water on which it

could swim and dive, but was avoided by all other animals, because of its ugly

appearance. Autumn came, and the leaves in the forest turned to orange and

gold. then, as winter approached, the wind caught them as they fell and whirled

them in the cold air. The clouds, heavy with hail and snow-flakes, hung low in

the sky, and the raven stood on the ferns crying, “Croak, croak.” It made one

shiver with cold to look at him. All this was very sad for the poor little

duckling. One evening, just as the sun set amid radiant clouds, there came a

large flock of beautiful birds out of the bushes. The duckling had never seen

any like them before. They were swans, and they curved their graceful necks,

while their soft plumage shown with dazzling whiteness. They uttered a singular

cry, as they spread their glorious wings and flew away from those cold regions

to warmer countries across the sea. As they mounted higher and higher in the

air, the ugly little duckling felt quite a strange sensation as he watched

them. He whirled himself in the water like a wheel, stretched out his neck

towards them, and uttered a cry so strange that it frightened himself. Could he

ever forget those beautiful, happy birds; and when at last they were out of his

sight, he dived under the water, and rose again almost beside himself with

excitement. He knew not the names of these birds, nor where they had flown, but

he felt towards them as he had never felt for any other bird in the world. He

was not envious of these beautiful creatures, but wished to be as lovely as

they. Poor ugly creature, how gladly he would have lived even with the ducks

had they only given him encouragement. The winter grew colder and colder; he

was obliged to swim about on the water to keep it from freezing, but every

night the space on which he swam became smaller and smaller. At length it froze

so hard that the ice in the water crackled as he moved, and the duckling had to

paddle with his legs as well as he could, to keep the space from closing up. He

became exhausted at last, and lay still and helpless, frozen fast in the ice.

Early in the

morning, a peasant, who was passing by, saw what had happened. He broke the ice

in pieces with his wooden shoe, and carried the duckling home to his wife. The

warmth revived the poor little creature; but when the children wanted to play

with him, the duckling thought they would do him some harm; so he started up in

terror, fluttered into the milk-pan, and splashed the milk about the room. Then

the woman clapped her hands, which frightened him still more. He flew first

into the butter-cask, then into the meal-tub, and out again. What a condition

he was in! The woman screamed, and struck at him with the tongs; the children

laughed and screamed, and tumbled over each other, in their efforts to catch

him; but luckily he escaped. The door stood open; the poor creature could just

manage to slip out among the bushes, and lie down quite exhausted in the newly

fallen snow.

It would be very

sad, were I to relate all the misery and privations which the poor little

duckling endured during the hard winter; but when it had passed, he found

himself lying one morning in a moor, amongst the rushes. He felt the warm sun

shining, and heard the lark singing, and saw that all around was beautiful

spring. Then the young bird felt that his wings were strong, as he flapped them

against his sides, and rose high into the air. They bore him onwards, until he

found himself in a large garden, before he well knew how it had happened. The

apple-trees were in full blossom, and the fragrant elders bent their long green

branches down to the stream which wound round a smooth lawn. Everything looked

beautiful, in the freshness of early spring. From a thicket close by came three

beautiful white swans, rustling their feathers, and swimming lightly over the

smooth water. The duckling remembered the lovely birds, and felt more strangely

unhappy than ever.

“I will fly to

those royal birds,” he exclaimed, “and they will kill me, because I am so ugly,

and dare to approach them; but it does not matter: better be killed by them

than pecked by the ducks, beaten by the hens, pushed about by the maiden who

feeds the poultry, or starved with hunger in the winter.”

Then he flew to

the water, and swam towards the beautiful swans. The moment they espied the

stranger, they rushed to meet him with outstretched wings.

“Kill me,” said

the poor bird; and he bent his head down to the surface of the water, and

awaited death.

But what did he

see in the clear stream below? His own image; no longer a dark, gray bird, ugly

and disagreeable to look at, but a graceful and beautiful swan. To be born in a

duck’s nest, in a farmyard, is of no consequence to a bird, if it is hatched

from a swan’s egg. He now felt glad at having suffered sorrow and trouble,

because it enabled him to enjoy so much better all the pleasure and happiness

around him; for the great swans swam round the new-comer, and stroked his neck

with their beaks, as a welcome.

Into the garden

presently came some little children, and threw bread and cake into the water.

“See,” cried the

youngest, “there is a new one;” and the rest were delighted, and ran to their

father and mother, dancing and clapping their hands, and shouting joyously,

“There is another swan come; a new one has arrived.”

Then they threw

more bread and cake into the water, and said, “The new one is the most

beautiful of all; he is so young and pretty.” And the old swans bowed their

heads before him.

Then he felt

quite ashamed, and hid his head under his wing; for he did not know what to do,

he was so happy, and yet not at all proud. He had been persecuted and despised

for his ugliness, and now he heard them say he was the most beautiful of all

the birds. Even the elder-tree bent down its bows into the water before him,

and the sun shone warm and bright. Then he rustled his feathers, curved his

slender neck, and cried joyfully, from the depths of his heart, “I never

dreamed of such happiness as this, while I was an ugly duckling.”

Friday 27 September 2019

Friday's Sund Word: "Minha Cabrocha" by Lamartine Babo (in Portuguese)

Para fazer meu samba não tirei diploma

Cabrocha bonita, nascida na roça, tem aroma

Quando vem da igreja, Lá da Freguesia,

Traz no olhar, feitiçaria

Traz no olhar feitiçaria

Quer se casar numa igreja e na Pretoria

Cabrocha assim, gosto de ver

Não põe carmim mas faz endoidecer.

Vou ajuntar um dinheirinho

Para fazer uma casa lá no campinho...

Lá, cabrochinha flor e mulher

Hás de ser minha enquanto Deus quiser

Cabrocha bonita, nascida na roça, tem aroma

Quando vem da igreja, Lá da Freguesia,

Traz no olhar, feitiçaria

Traz no olhar feitiçaria

Quer se casar numa igreja e na Pretoria

Cabrocha assim, gosto de ver

Não põe carmim mas faz endoidecer.

Vou ajuntar um dinheirinho

Para fazer uma casa lá no campinho...

Lá, cabrochinha flor e mulher

Hás de ser minha enquanto Deus quiser

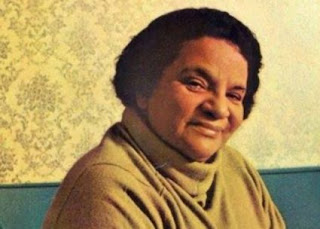

You can hear "Minha Cabrocha" sung by Aracy de Almeida and the Turma da Vila band here.

Thursday 26 September 2019

Thursday's Serial: "The Brass Bottle" by F. Anstey (in English) - I

CHAPTER I -

HORACE VENTIMORE RECEIVES A COMMISSION

"This

day six weeks—just six weeks ago!" Horace Ventimore said, half aloud, to

himself, and pulled out his watch. "Half-past twelve—what was I doing at

half-past twelve?"

As

he sat at the window of his office in Great Cloister Street, Westminster, he

made his thoughts travel back to a certain glorious morning in August which now

seemed so remote and irrecoverable. At this precise time he was waiting on the

balcony of the Hôtel de la Plage—the sole hostelry of St. Luc-en-Port, the tiny

Normandy watering-place upon which, by some happy inspiration, he had lighted

during a solitary cycling tour—waiting until She should appear.

He

could see the whole scene: the tiny cove, with the violet shadow of the cliff

sleeping on the green water; the swell of the waves lazily lapping against the

diving-board from which he had plunged half an hour before; he remembered the

long swim out to the buoy; the exhilarated anticipation with which he had

dressed and climbed the steep path to the hotel terrace.

For

was he not to pass the whole remainder of that blissful day in Sylvia Futvoye's

society? Were they not to cycle together (there were, of course, others of the party—but they did not count), to cycle over to Veulettes, to picnic

there under the cliff, and ride back—always together—in the sweet-scented dusk,

over the slopes, between the poplars or the cornfields glowing golden against a

sky of warm purple?

Now

he saw himself going round to the gravelled courtyard in front of the hotel

with a sudden dread of missing her. There was nothing there but the little low

cart, with its canvas tilt which was to convey Professor Futvoye and his wife

to the place of rendezvous.

There

was Sylvia at last, distractingly fair and fresh in her cool pink blouse and cream-coloured

skirt; how gracious and friendly and generally delightful she had been

throughout that unforgettable day, which was supreme amongst others only a

little less perfect, and all now fled for ever!

They

had had drawbacks, it was true. Old Futvoye was perhaps the least bit of a bore

at times, with his interminable disquisitions on Egyptian art and ancient

Oriental character-writing, in which he seemed convinced that Horace must feel

a perfervid interest, as, indeed, he thought it politic to affect. The

Professor was a most learned archæologist, and positively bulged with

information on his favourite subjects; but it is just possible that Horace

might have been less curious concerning the distinction between Cuneiform and

Aramæan or Kufic and Arabic inscriptions if his informant had happened to be

the father of anybody else. However, such insincerities as these are but so

many evidences of sincerity.

So

with self-tormenting ingenuity Horace conjured up various pictures from that

Norman holiday of his: the little half-timbered cottages with their faded blue

shutters and the rushes growing out of their thatch roofs; the spires of

village churches gleaming above the bronze-green beeches; the bold headlands,

their ochre and yellow cliffs contrasting grimly with the soft ridges of the

turf above them; the tethered black-and-white cattle grazing peacefully

against a background of lapis lazuli and malachite sea, and in every scene the

sensation of Sylvia's near presence, the sound of her voice in his ears. And

now?... He looked up from the papers and tracing-cloth on his desk, and round

the small panelled room which served him as an office, at the framed plans and

photographs, the set squares and T squares on the walls, and felt a dull

resentment against his surroundings. From his window he commanded a cheerful

view of a tall, mouldering wall, once part of the Abbey boundaries, surmounted

by chevaux-de-frise, above whose rust-attenuated spikes some plane trees

stretched their yellowing branches.

"She

would have come to care for me," Horace's thoughts ran on, disjointedly.

"I could have sworn that that last day of all—and her people didn't seem

to object to me. Her mother asked me cordially enough to call on them when they

were back in town. When I did—"

When he had called, there had been a

difference—not an unusual sequel to an acquaintanceship begun in a Continental

watering-place. It was difficult to define, but unmistakable—a certain

formality and constraint on Mrs. Futvoye's part, and even on Sylvia's, which

seemed intended to warn him that it is not every friendship that survives the

Channel passage. So he had gone away sore at heart, but fully recognising that

any advances in future must come from their side. They might ask him to dinner,

or at least to call again; but more than a month had passed, and they had made

no sign. No, it was all over; he must consider himself dropped.

"After

all," he told himself, with a short and anything but mirthful laugh,

"it's natural enough. Mrs. Futvoye has probably been making inquiries

about my professional prospects. It's better as it is. What earthly chance have

I got of marrying unless I can get work of my own? It's all I can do to keep

myself decently. I've no right to dream of asking any one—to say nothing

of Sylvia—to marry me. I should only be rushing into temptation if I saw any

more of her. She's not for a poor beggar like me, who was born unlucky. Well,

whining won't do any good—let's have a look at Beevor's latest

performance."

He

spread out a large coloured plan, in a corner of which appeared the name of

"William Beevor, Architect," and began to study it in a spirit of

anything but appreciation.

"Beevor

gets on," he said to himself. "Heaven knows that I don't grudge him

his success. He's a good fellow—though he does build architectural atrocities,

and seem to like 'em. Who am I to give myself airs? He's successful—I'm not.

Yet if I only had his opportunities, what wouldn't I make of them!"

Let

it be said here that this was not the ordinary self-delusion of an incompetent.

Ventimore really had talent above the average, with ideals and ambitions which

might under better conditions have attained recognition and fulfilment before

this.

But

he was not quite energetic enough, besides being too proud, to push himself

into notice, and hitherto he had met with persistent ill-luck.

So

Horace had no other occupation now but to give Beevor, whose offices and clerk

he shared, such slight assistance as he might require, and it was by no means

cheering to feel that every year of this enforced semi-idleness left him

further handicapped in the race for wealth and fame, for he had already passed

his twenty-eighth birthday.

If

Miss Sylvia Futvoye had indeed felt attracted towards him at one time it was

not altogether incomprehensible. Horace Ventimore was not a model of manly

beauty—models of manly beauty are rare out of novels, and seldom interesting in

them; but his clear-cut, clean-shaven face possessed a certain distinction, and

if there were faint satirical lines about the mouth, they were redeemed

by the expression of the grey-blue eyes, which were remarkably frank and

pleasant. He was well made, and tall enough to escape all danger of being

described as short; fair-haired and pale, without being unhealthily pallid, in

complexion, and he gave the impression of being a man who took life as it came,

and whose sense of humour would serve as a lining for most clouds that might

darken his horizon.

There

was a rap at the door which communicated with Beevor's office, and Beevor

himself, a florid, thick-set man, with small side-whiskers, burst in.

"I

say, Ventimore, you didn't run off with the plans for that house I'm building

at Larchmere, did you? Because—ah, I see you're looking over them. Sorry to

deprive you, but—"

"Thanks, old fellow, take them, by all means.

I've seen all I wanted to see."

"Well, I'm just off to Larchmere now. Want to

be there to check the quantities, and there's my other house at Fittlesdon. I

must go on afterwards and set it out, so I shall probably be away some days.

I'm taking Harrison down, too. You won't be wanting him, eh?"

Ventimore laughed. "I can manage to do

nothing without a clerk to help me. Your necessity is greater than mine. Here

are the plans."

"I'm rather pleased with 'em myself, you

know," said Beevor; "that roof ought to look well, eh? Good idea of

mine lightening the slate with that ornamental tile-work along the top. You saw

I put in one of your windows with just a trifling addition. I was almost

inclined to keep both gables alike, as you suggested, but it struck me a little

variety—one red brick and the other 'parged'—would be more

out-of-the-way."

"Oh, much," agreed Ventimore, knowing

that to disagree was useless.

"Not, mind you," continued Beevor,

"that I believe in going in for too much originality in domestic architecture. The average client no more wants an original house than he

wants an original hat; he wants something he won't feel a fool in. I've often

thought, old man, that perhaps the reason why you haven't got on—you don't mind

my speaking candidly, do you?"

"Not a bit," said Ventimore, cheerfully.

"Candour's the cement of friendship. Dab it on."

"Well, I was only going to say that you do

yourself no good by all those confoundedly unconventional ideas of yours. If

you had your chance to-morrow, it's my belief you'd throw it away by insisting

on some fantastic fad or other."

"These speculations are a trifle premature,

considering that there doesn't seem the remotest prospect of my ever getting a

chance at all."

"I got mine before I'd set up six

months," said Beevor. "The great thing, however," he went on,

with a flavour of personal application, "is to know how to use it when it

does come. Well, I must be off if I mean to catch that one o'clock from

Waterloo. You'll see to anything that may come in for me while I'm away, won't

you, and let me know? Oh, by the way, the quantity surveyor has just sent in

the quantities for that schoolroom at Woodford—do you mind running through them

and seeing they're right? And there's the specification for the new wing at

Tusculum Lodge—you might draft that some time when you've nothing else to do.

You'll find all the papers on my desk. Thanks awfully, old chap."

And Beevor hurried back to his own room, where for

the next few minutes he could be heard bustling Harrison, the clerk, to make

haste; then a hansom was whistled for, there were footsteps down the old

stairs, the sounds of a departing vehicle on the uneven stones, and after that

silence and solitude.

It was not in Nature to avoid feeling a little

envious. Beevor had work to do in the world: even if it chiefly consisted in

profaning sylvan retreats by smug or pretentious villas, it was still

work which entitled him to consideration and respect in the eyes of all

right-minded persons.

And nobody believed in Horace; as yet he had never

known the satisfaction of seeing the work of his brain realised in stone and

brick and mortar; no building stood anywhere to bear testimony to his existence

and capability long after he himself should have passed away.

It was not a profitable train of thought, and, to

escape from it, he went into Beevor's room and fetched the documents he had

mentioned—at least they would keep him occupied until it was time to go to his

club and lunch. He had no sooner settled down to his calculations, however,

when he heard a shuffling step on the landing, followed by a knock at Beevor's

office-door. "More work for Beevor," he thought; "what luck the

fellow has! I'd better go in and explain that he's just left town on business."

But on entering the adjoining room he heard the

knocking repeated—this time at his own door; and hastening back to put an end

to this somewhat undignified form of hide-and-seek, he discovered that this

visitor at least was legitimately his, and was, in fact, no other than

Professor Anthony Futvoye himself.

The Professor was standing in the doorway peering

short-sightedly through his convex glasses, his head protruded from his

loosely-fitting great-coat with an irresistible suggestion of an inquiring

tortoise. To Horace his appearance was more welcome than that of the wealthiest

client—for why should Sylvia's father take the trouble to pay him this visit

unless he still wished to continue the acquaintanceship? It might even be that

he was the bearer of some message or invitation.

So, although to an impartial eye the Professor

might not seem the kind of elderly gentleman whose society would produce any

wild degree of exhilaration, Horace was unfeignedly delighted to see him.

"Extremely kind of you to come and see me

like this, sir," he said warmly, after establishing him in the solitary

armchair reserved for hypothetical clients.

"Not at all. I'm afraid your visit to

Cottesmore Gardens some time ago was somewhat of a disappointment."

"A disappointment?" echoed Horace, at a

loss to know what was coming next.

"I refer to the fact—which possibly, however,

escaped your notice"—explained the Professor, scratching his scanty patch

of grizzled whisker with a touch of irascibility, "that I myself was not

at home on that occasion."

"Indeed, I was greatly disappointed,"

said Horace, "though of course I know how much you are engaged. It's all

the more good of you to spare time to drop in for a chat just now."

"I've not come to chat, Mr. Ventimore. I

never chat. I wanted to see you about a matter which I thought you might be so

obliging as to— But I observe you are busy—probably too busy to attend to such

a small affair."

It was clear enough now; the Professor was going

to build, and had decided—could it be at Sylvia's suggestion?—to entrust the

work to him! But he contrived to subdue any self-betraying eagerness, and reply

(as he could with perfect truth) that he had nothing on hand just then which he

could not lay aside, and that if the Professor would let him know what he

required, he would take it up at once.

"So much the better," said the

Professor; "so much the better. Both my wife and daughter declared that it

was making far too great a demand upon your good nature; but, as I told them,

'I am much mistaken,' I said, 'if Mr. Ventimore's practice is so extensive that

he cannot leave it for one afternoon—'"

Evidently it was not a house. Could he be needed

to escort them somewhere that afternoon? Even that was more than he had hoped

for a few minutes since. He hastened to repeat that he was perfectly free

that afternoon.

"In that case," said the Professor,

beginning to fumble in all his pockets—was he searching for a note in Sylvia's

handwriting?—"in that case, you will be conferring a real favour on me if you

can make it convenient to attend a sale at Hammond's Auction Rooms in Covent

Garden, and just bid for one or two articles on my behalf."

Whatever disappointment Ventimore felt, it may be

said to his credit that he allowed no sign of it to appear. "Of course

I'll go, with pleasure," he said, "if I can be of any use."

"I knew I shouldn't come to you in

vain," said the Professor. "I remembered your wonderful good nature,

sir, in accompanying my wife and daughter on all sorts of expeditions in the

blazing hot weather we had at St. Luc—when you might have remained quietly at

the hotel with me. Not that I should trouble you now, only I have to lunch at

the Oriental Club, and I've an appointment afterwards to examine and report on

a recently-discovered inscribed cylinder for the Museum, which will fully

occupy the rest of the afternoon, so that it's physically impossible for me to

go to Hammond's myself, and I strongly object to employing a broker when I can

avoid it. Where did I put that catalogue?... Ah, here it is. This was sent to

me by the executors of my old friend, General Collingham, who died the other

day. I met him at Nakada when I was out excavating some years ago. He was

something of a collector in his way, though he knew very little about it, and,

of course, was taken in right and left. Most of his things are downright

rubbish, but there are just a few lots that are worth securing, at a reasonable

figure, by some one who knew what he was about."

"But, my dear Professor," remonstrated

Horace, not relishing this responsibility, "I'm afraid I'm as likely as

not to pick up some of the rubbish. I've no special knowledge of Oriental

curios."

"At St. Luc," said the Professor,

"you impressed me as having, for an amateur, an exceptionally accurate and

comprehensive acquaintance with Egyptian and Arabian art from the earliest

period." (If this were so, Horace could only feel with shame what a

fearful humbug he must have been.) "However, I've no wish to lay too heavy

a burden on you, and, as you will see from this catalogue, I have ticked off

the lots in which I am chiefly interested, and made a note of the limit to

which I am prepared to bid, so you'll have no difficulty."

"Very well," said Horace; "I'll go

straight to Covent Garden, and slip out and get some lunch later on."

"Well, perhaps, if you don't mind. The lots I

have marked seem to come on at rather frequent intervals, but don't let that

consideration deter you from getting your lunch, and if you should miss

anything by not being on the spot, why, it's of no consequence, though I don't

say it mightn't be a pity. In any case, you won't forget to mark what each lot

fetches, and perhaps you wouldn't mind dropping me a line when you return the

catalogue—or stay, could you look in some time after dinner this evening, and

let me know how you got on?—that would be better."

Horace thought it would be decidedly better, and

undertook to call and render an account of his stewardship that evening. There

remained the question of a deposit, should one or more of the lots be knocked

down to him; and, as he was obliged to own that he had not so much as ten

pounds about him at that particular moment, the Professor extracted a note for

that amount from his case, and handed it to him with the air of a benevolent

person relieving a deserving object. "Don't exceed my limits," he

said, "for I can't afford more just now; and mind you give Hammond your

own name, not mine. If the dealers get to know I'm after the things, they'll

run you up. And now, I don't think I need detain you any longer, especially as

time is running on. I'm sure I can trust you to do the best you can for

me. Till this evening, then."

A few minutes later Horace was driving up to

Covent Garden behind the best-looking horse he could pick out.

The Professor might have required from him rather

more than was strictly justified by their acquaintanceship, and taken his

acquiescence too much as a matter of course—but what of that? After all, he was

Sylvia's parent.

"Even with my luck," he was thinking,

"I ought to succeed in getting at least one or two of the lots he's

marked; and if I can only please him, something may come of it."

And in this sanguine mood Horace entered Messrs.

Hammond's well-known auction rooms.

CHAPTER II - A CHEAP LOT

In spite of the fact that it was the luncheon hour

when Ventimore reached Hammond's Auction Rooms, he found the big, skylighted

gallery where the sale of the furniture and effects of the late General

Collingham was proceeding crowded to a degree which showed that the deceased

officer had some reputation as a connoisseur.

The narrow green baize tables below the

auctioneer's rostrum were occupied by professional dealers, one or two of them

women, who sat, paper and pencil in hand, with much the same air of apparent

apathy and real vigilance that may be noticed in the Casino at Monte Carlo.

Around them stood a decorous and businesslike crowd, mostly dealers, of various

types. On a magisterial-looking bench sat the auctioneer, conducting the sale

with a judicial impartiality and dignity which forbade him, even in his most

laudatory comments, the faintest accent of enthusiasm.

The October sunshine, striking through the glazed

roof, re-gilded the tarnished gas-stars, and suffused the dusty atmosphere with

palest gold. But somehow the utter absence of excitement in the crowd, the

calm, methodical tone of the auctioneer, and the occasional mournful cry of

"Lot here, gentlemen!" from the porter when any article was too large

to move, all served to depress Ventimore's usually mercurial spirits.

For all Horace knew, the collection as a whole

might be of little value, but it very soon became clear that others besides

Professor Futvoye had singled out such gems as there were, also that the

Professor had considerably under-rated the prices they were likely to

fetch.

Ventimore made his bids with all possible

discretion, but time after time he found the competition for some perforated

mosque lantern, engraved ewer, or ancient porcelain tile so great that his

limit was soon reached, and his sole consolation was that the article

eventually changed hands for sums which were very nearly double the Professor's

estimate.

Several dealers and brokers, despairing of a

bargain that day, left, murmuring profanities; most of those who remained

ceased to take a serious interest in the proceedings, and consoled themselves

with cheap witticisms at every favourable occasion.

The sale dragged slowly on, and, what with

continual disappointment and want of food, Horace began to feel so weary that

he was glad, as the crowd thinned, to get a seat at one of the green baize

tables, by which time the skylights had already changed from livid grey to

slate colour in the deepening dusk.

A couple of meek Burmese Buddhas had just been put

up, and bore the indignity of being knocked down for nine-and-sixpence the pair

with dreamy, inscrutable simpers; Horace only waited for the final lot marked

by the Professor—an old Persian copper bowl, inlaid with silver and engraved

round the rim with an inscription from Hafiz.

The limit to which he was authorised to go was two

pounds ten; but, so desperately anxious was Ventimore not to return

empty-handed, that he had made up his mind to bid an extra sovereign if

necessary, and say nothing about it.

However, the bowl was put up, and the bidding soon

rose to three pounds ten, four pounds, four pounds ten, five pounds, five

guineas, for which last sum it was acquired by a bearded man on Horace's right,

who immediately began to regard his purchase with a more indulgent eye.

Ventimore had done his best, and failed; there was

no reason now why he should stay a moment longer—and yet he sat on, from sheer

fatigue and disinclination to move.

"Now we come to Lot 254, gentlemen," he

heard the auctioneer saying, mechanically; "a capital Egyptian mummy-case

in fine con— No, I beg pardon, I'm wrong. This is an article which by some

mistake has been omitted from the catalogue, though it ought to have been in

it. Everything on sale to-day, gentlemen, belonged to the late General

Collingham. We'll call this No. 253a. Antique brass bottle. Very curious."

One of the porters carried the bottle in between

the tables, and set it down before the dealers at the farther end with a tired

nonchalance.

It was an old, squat, pot-bellied vessel, about

two feet high, with a long thick neck, the mouth of which was closed by a sort

of metal stopper or cap; there was no visible decoration on its sides, which

were rough and pitted by some incrustation that had formed on them, and been

partially scraped off. As a piece of bric-à-brac it certainly possessed few

attractions, and there was a marked tendency to "guy" it among the

more frivolous brethren.

"What do you call this, sir?" inquired

one of the auctioneer, with the manner of a cheeky boy trying to get a rise out

of his form-master. "Is it as 'unique' as the others?"

"You're as well able to judge as I am,"

was the guarded reply. "Any one can see for himself it's not modern

rubbish."

"Make a pretty little ornament for the

mantelpiece!" remarked a wag.

"Is the top made to unscrew, or what,

sir?" asked a third. "Seems fixed on pretty tight."

"I can't say. Probably it has not been

removed for some time."

"It's a goodish weight," said the chief

humorist, after handling it. "What's inside of it, sir—sardines?"

"I don't represent it as having anything

inside it," said the auctioneer. "If you want to know my opinion, I

think there's money in it."

"'Ow much?"

"Don't misunderstand me, gentlemen. When I

say I consider there's money in it, I'm not alluding to its contents. I've no

reason to believe that it contains anything. I'm merely suggesting the thing

itself may be worth more than it looks."

"Ah, it might be that without 'urting

itself!"

"Well, well, don't let us waste time. Look

upon it as a pure speculation, and make me an offer for it, some of you.

Come."

"Tuppence-'ap'ny!" cried the comic man,

affecting to brace himself for a mighty effort.

"Pray be serious, gentlemen. We want to get

on, you know. Anything to make a start. Five shillings? It's not the value of

the metal, but I'll take the bid. Six. Look at it well. It's not an article you

come across every day of your lives."

The bottle was still being passed round with

disrespectful raps and slaps, and it had now come to Ventimore's right-hand

neighbour, who scrutinised it carefully, but made no bid.

"That's all right, you know," he

whispered in Horace's ear. "That's good stuff, that is. If I was you, I'd

'ave that."

"Seven shillings—eight—nine bid for it over

there in the corner," said the auctioneer.

"If you think it's so good, why don't you

have it yourself?" Horace asked his neighbour.

"Me? Oh, well, it ain't exactly in my line,

and getting this last lot pretty near cleaned me out. I've done for to-day, I

'ave. All the same, it is a curiosity; dunno as I've seen a brass vawse just

that shape before, and it's genuine old, though all these fellers are too

ignorant to know the value of it. So I don't mind giving you the tip."

Horace rose, the better to examine the top. As far

as he could make out in the flickering light of one of the gas-stars, which the

auctioneer had just ordered to be lit, there were half-erased scratches and

triangular marks on the cap that might possibly be an inscription. If so, might

there not be the means here of regaining the Professor's favour, which he felt

that, as it was, he should probably forfeit, justly or not, by his ill-success?

He could hardly spend the Professor's money on it,

since it was not in the catalogue, and he had no authority to bid for it, but

he had a few shillings of his own to spare. Why not bid for it on his own

account as long as he could afford to do so? If he were outbid, as usual, it

would not particularly matter.

"Thirteen shillings," the auctioneer was

saying, in his dispassionate tones. Horace caught his eye, and slightly raised

his catalogue, while another man nodded at the same time. "Fourteen in two

places." Horace raised his catalogue again. "I won't go beyond

fifteen," he thought.

"Fifteen. It's against you, sir. Any advance

on fifteen? Sixteen—this very quaint old Oriental bottle going for only sixteen

shillings.

"After all," thought Horace, "I

don't mind anything under a pound for it." And he bid seventeen shillings.

"Eighteen," cried his rival, a short, cheery, cherub-faced little

dealer, whose neighbours adjured him to "sit quiet like a good little boy

and not waste his pocket-money."

"Nineteen!" said Horace.

"Pound!" answered the cherubic man.

"A pound only bid for this grand brass

vessel," said the auctioneer, indifferently. "All done at a

pound?"

Horace thought another shilling or two would not

ruin him, and nodded.

"A guinea. For the last time. You'll lose it,

sir," said the auctioneer to the little man.

"Go on, Tommy. Don't you be beat. Spring

another bob on it, Tommy," his friends advised him ironically; but

Tommy shook his head, with the air of a man who knows when to draw the line.

"One guinea—and that's not half its value! Gentleman on my left,"

said the auctioneer, more in sorrow than in anger—and the brass bottle became

Ventimore's property.

He paid for it, and, since he could hardly walk

home nursing a large metal bottle without attracting an inconvenient amount of

attention, directed that it should be sent to his lodgings at Vincent Square.

But when he was out in the fresh air, walking

westward to his club, he found himself wondering more and more what could have

possessed him to throw away a guinea—when he had few enough for legitimate expenses—on

an article of such exceedingly problematical value.

CHAPTER III - AN UNEXPECTED

OPENING

Ventimore made his way to Cottesmore Gardens that

evening in a highly inconsistent, not to say chaotic, state of mind. The

thought that he would presently see Sylvia again made his blood course quicker,

while he was fully determined to say no more to her than civility demanded.

At one moment he was blessing Professor Futvoye

for his happy thought in making use of him; at another he was bitterly recognising

that it would have been better for his peace of mind if he had been left alone.

Sylvia and her mother had no desire to see more of him; if they had, they would

have asked him to come before this. No doubt they would tolerate him now for

the Professor's sake; but who would not rather be ignored than tolerated?

The more often he saw Sylvia the more she would

make his heart ache with vain longing—whereas he was getting almost reconciled

to her indifference; he would very soon be cured if he didn't see her.

Why should he see her? He need not go in at all.

He had merely to leave the catalogue with his compliments, and the Professor

would learn all he wanted to know.

On second thoughts he must go in—if only to return

the bank-note. But he would ask to see the Professor in private. Most probably

he would not be invited to join his wife and daughter, but if he were, he could

make some excuse. They might think it a little odd—a little discourteous,

perhaps; but they would be too relieved to care much about that.

When he got to Cottesmore Gardens, and was

actually at the door of the Futvoyes' house, one of the neatest and demurest in

that retired and irreproachable quarter, he began to feel a craven hope that

the Professor might be out, in which case he need only leave the catalogue and

write a letter when he got home, reporting his non-success at the sale, and

returning the note.

And, as it happened, the Professor was out, and

Horace was not so glad as he thought he should be. The maid told him that the

ladies were in the drawing-room, and seemed to take it for granted that he was

coming in, so he had himself announced. He would not stay long—just long enough

to explain his business there, and make it clear that he had no wish to force

his acquaintance upon them. He found Mrs. Futvoye in the farther part of the

pretty double drawing-room, writing letters, and Sylvia, more dazzlingly fair

than ever in some sort of gauzy black frock with a heliotrope sash and a bunch

of Parma violets on her breast, was comfortably established with a book in the

front room, and seemed surprised, if not resentful, at having to disturb

herself.

"I must apologise," he began, with an

involuntary stiffness, "for calling at this very unceremonious time; but

the fact is, the Professor—"

"I know all about it," interrupted Mrs.

Futvoye, brusquely, while her shrewd, light-grey eyes took him in with a cool

stare that was humorously observant without being aggressive. "We heard

how shamefully my husband abused your good-nature. Really, it was too bad of

him to ask a busy man like you to put aside his work and go and spend a whole

day at that stupid auction!"

"Oh, I'd nothing particular to do. I can't

call myself a busy man—unfortunately," said Horace, with that frankness

which scorns to conceal what other people know perfectly well already.

"Ah, well, it's very nice of you to make

light of it; but he ought not to have done it—after so short an

acquaintance, too. And to make it worse, he has had to go out unexpectedly this

evening, but he'll be back before very long if you don't mind waiting."

"There's really no need to wait," said

Horace, "because this catalogue will tell him everything, and, as the

particular things he wanted went for much more than he thought, I wasn't able

to get any of them."

"I'm sure I'm very glad of it," said

Mrs. Futvoye, "for his study is crammed with odds and ends as it is, and I

don't want the whole house to look like a museum or an antiquity shop. I'd all

the trouble in the world to persuade him that a great gaudy gilded mummy-case

was not quite the thing for a drawing-room. But, please sit down, Mr.

Ventimore."

"Thanks," stammered Horace,

"but—but I mustn't stay. If you will tell the Professor how sorry I was to

miss him, and—and give him back this note which he left with me to cover any

deposit, I—I won't interrupt you any longer."

He was, as a rule, imperturbable in most social

emergencies, but just now he was seized with a wild desire to escape, which, to

his infinite mortification, made him behave like a shy schoolboy.

"Nonsense!" said Mrs. Futvoye; "I

am sure my husband would be most annoyed if we didn't keep you till he

came."

"I really ought to go," he declared,

wistfully enough.

"We mustn't tease Mr. Ventimore to stay,

mother, when he so evidently wants to go," said Sylvia, cruelly.

"Well, I won't detain you—at least, not long.

I wonder if you would mind posting a letter for me as you pass the pillar-box?

I've almost finished it, and it ought to go to-night, and my maid Jessie has

such a bad cold I really don't like sending her out with it."

It would have been impossible to refuse to stay

after that—even if he had wished. It would only be for a few minutes. Sylvia

might spare him that much of her time. He should not trouble her again.

So Mrs. Futvoye went back to her bureau, and Sylvia and he were practically

alone.

She had taken a seat not far from his, and made a

few constrained remarks, obviously out of sheer civility. He returned

mechanical replies, with a dreary wonder whether this could really be the girl

who had talked to him with such charming friendliness and confidence only a few

weeks ago in Normandy.

And the worst of it was, she was looking more

bewitching than ever; her slim arms gleaming through the black lace of her

sleeves, and the gold threads in her soft masses of chestnut hair sparkling in

the light of the shaded lamp behind her. The slight contraction of her eyebrows

and the mutinous downward curve of her mouth seemed expressive of boredom.

"What a dreadfully long time mamma is over

that letter!" she said at last. "I think I'd better go and hurry her

up."

"Please don't—unless you are particularly

anxious to get rid of me."

"I thought you seemed particularly anxious to

escape," she said coldly. "And, as a family, we have certainly taken

up quite enough of your time for one day."

"That is not the way you used to talk at St.

Luc!" he said.

"At St. Luc? Perhaps not. But in London

everything is so different, you see."

"Very different."

"When one meets people abroad who—who seem at

all inclined to be sociable," she continued, "one is so apt to think

them pleasanter than they really are. Then one meets them again, and—and wonders

what one ever saw to like in them. And it's no use pretending one feels the

same, because they generally understand sooner or later. Don't you find

that?"

"I do, indeed," he said, wincing,

"though I don't know what I've done to deserve that you should tell me

so!"

"Oh, I was not blaming you. You have been

most angelic. I can't think how papa could have expected you to take all that

trouble for him—still, you did, though you must have simply hated it."

"But, good heavens! don't you know I should

be only too delighted to be of the least service to him—or to any of you?"

"You looked anything but delighted when you

came in just now; you looked as if your one idea was to get it over as soon as

you could. You know perfectly well you're longing now for mother to finish her

letter and set you free. Do you really think I can't see that?"

"If all that is true, or partly true,"

said Horace, "can't you guess why?"

"I guessed how it was when you called here

first that afternoon. Mamma had asked you to, and you thought you might as well

be civil; perhaps you really did think it would be pleasant to see us again—but

it wasn't the same thing. Oh, I saw it in your face directly—you became

conventional and distant and horrid, and it made me horrid too; and you went

away determined that you wouldn't see any more of us than you could help.

That's why I was so furious when I heard that papa had been to see you, and

with such an object."

All this was so near the truth, and yet missed it

with such perverse ingenuity, that Horace felt bound to put himself right.

"Perhaps I ought to leave things as they

are," he said, "but I can't. It's no earthly use, I know; but may I

tell you why it really was painful to me to meet you again? I thought you were

changed, that you wished to forget, and wished me to forget—only I can't—that

we had been friends for a short time. And though I never blamed you—it was

natural enough—it hit me pretty hard—so hard that I didn't feel anxious to

repeat the experience."

"Did it hit you hard?" said Sylvia,

softly. "Perhaps I minded too, just a very little. However,"

she added, with a sudden smile, that made two enchanting dimples in her cheeks,

"it only shows how much more sensible it is to have things out. Now

perhaps you won't persist in keeping away from us?"

"I believe," said Horace, gloomily,

still determined not to let any direct avowal pass his lips, "it would be

best that I should keep away."

Her half-closed eyes shone through their long

lashes; the violets on her breast rose and fell. "I don't think I

understand," she said, in a tone that was both hurt and offended.

There is a pleasure in yielding to some

temptations that more than compensates for the pain of any previous resistance.

Come what might, he was not going to be misunderstood any longer.

"If I must tell you," he said,

"I've fallen desperately, hopelessly, in love with you. Now you know the

reason."

"It doesn't seem a very good reason for

wanting to go away and never see me again. Does it?"

"Not when I've no right to speak to you of

love?"

"But you've done that!"

"I know," he said penitently; "I

couldn't help it. But I never meant to. It slipped out. I quite understand how

hopeless it is."

"Of course, if you are so sure as all that,

you are quite right not to try."

"Sylvia! You can't mean that—that you do

care, after all?"

"Didn't you really see?" she said, with

a low, happy laugh. "How stupid of you! And how dear!"

He caught her hand, which she allowed to rest

contentedly in his. "Oh, Sylvia! Then you do—you do! But, my God, what a

selfish brute I am! For we can't marry. It may be years before I can ask you to

come to me. You father and mother wouldn't hear of your being engaged to

me."

"Need they hear of it just yet, Horace?"

"Yes, they must. I should feel a cur if I

didn't tell your mother, at all events."

"Then you shan't feel a cur, for we'll go and

tell her together." And Sylvia rose and went into the farther room, and

put her arms round her mother's neck. "Mother darling," she said, in

a half whisper, "it's really all your fault for writing such very long

letters, but—but—we don't exactly know how we came to do it—but Horace and I

have got engaged somehow. You aren't very angry, are you?"

"I think you're both extremely foolish,"

said Mrs. Futvoye, as she extricated herself from Sylvia's arms and turned to

face Horace. "From all I hear, Mr. Ventimore, you're not in a position to

marry at present."

"Unfortunately, no" said Horace;

"I'm making nothing as yet. But my chance must come some day. I don't ask

you to give me Sylvia till then."

"And you know you like Horace, mother!"

pleaded Sylvia. "And I'm ready to wait for him, any time. Nothing will

induce me to give him up, and I shall never, never care for anybody else. So you

see you may just as well give us your consent!"

"I'm afraid I've been to blame," said

Mrs. Futvoye. "I ought to have foreseen this at St. Luc. Sylvia is our

only child, Mr. Ventimore, and I would far rather see her happily married than

making what is called a 'grand match.' Still, this really does seem rather

hopeless. I am quite sure her father would never approve of it. Indeed, it must

not be mentioned to him—he would only be irritated."

"So long as you are not against us,"

said Horace, "you won't forbid me to see her?"

"I believe I ought to," said Mrs.

Futvoye; "but I don't object to your coming here occasionally, as an

ordinary visitor. Only understand this—until you can prove to my husband's

satisfaction that you are able to support Sylvia in the manner she has been

accustomed to, there must be no formal engagement. I think I am entitled

to ask that of you."

She was so clearly within her rights, and so much

more indulgent than Horace had expected—for he had always considered her an

unsentimental and rather worldly woman—that he accepted her conditions almost

gratefully. After all, it was enough for him that Sylvia returned his love, and

that he should be allowed to see her from time to time.

"It's rather a pity," said Sylvia,

meditatively, a little later, when her mother had gone back to her

letter-writing, and she and Horace were discussing the future; "it's

rather a pity that you didn't manage to get something at that sale. It might

have helped you with papa."

"Well, I did get something on my own

account," he said, "though I don't know whether it is likely to do me

any good with your father." And he told her how he had come to acquire the

brass bottle.

"And you actually gave a guinea for it?"

said Sylvia, "when you could probably get exactly the same thing, only

better, at Liberty's for about seven-and-sixpence! Nothing of that sort has any

charms for papa, unless it's dirty and dingy and centuries old."

"This looks all that. I only bought it

because, though it wasn't down on the catalogue, I had a fancy that it might

interest the Professor."

"Oh!" cried Sylvia, clasping her pretty

hands, "if only it does, Horace! If it turns out to be tremendously rare

and valuable! I do believe dad would be so delighted that he'd consent to

anything. Ah, that's his step outside ... he's letting himself in. Now mind you

don't forget to tell him about that bottle."

The Professor did not seem in the sweetest of

humours as he entered the drawing-room. "Sorry I was obliged to be from

home, and there was nobody but my wife and daughter here to entertain you. But

I am glad you stayed—yes, I'm rather glad you stayed."

"So am I, sir," said Horace, and

proceeded to give his account of the sale, which did not serve to improve the Professor's temper. He thrust out his under lip at certain items in the

catalogue. "I wish I'd gone myself," he said; "that bowl, a

really fine example of sixteenth-century Persian work, going for only five

guineas! I'd willingly have given ten for it. There, there, I thought I could

have depended on you to use your judgment better than that!"

"If you remember, sir, you strictly limited

me to the sums you marked."

"Nothing of the sort," said the

Professor, testily; "my marginal notes were merely intended as

indications, no more. You might have known that if you had secured one of the

things at any price I should have approved."

Horace had no grounds for knowing anything of the

kind, and much reason for believing the contrary, but he saw no use in arguing

the matter further, and merely said he was sorry to have misunderstood.

"No doubt the fault was mine," said the

Professor, in a tone that implied the opposite. "Still, making every

allowance for inexperience in these matters, I should have thought it

impossible for any one to spend a whole day bidding at a place like Hammond's

without even securing a single article."

"But, dad," put in Sylvia, "Mr.

Ventimore did get one thing—on his own account. It's a brass bottle, not down

in the catalogue, but he thinks it may be worth something perhaps. And he'd

very much like to have your opinion."

"Tchah!" said the Professor. "Some

modern bazaar work, most probably. He'd better have kept his money. What was

this bottle of yours like, now, eh?"

Horace described it.

"H'm. Seems to be what the Arabs call a

'kum-kum,' probably used as a sprinkler, or to hold rose-water. Hundreds of 'em

about," commented the Professor, crustily.

"It had a lid, riveted or soldered on,"

said Horace; "the general shape was something like this ..." And he

made a rapid sketch from memory, which the Professor took reluctantly, and then

adjusted his glasses with some increase of interest.

"Ha—the form is antique, certainly. And the

top hermetically fastened, eh? That looks as if it might contain

something."

"You don't think it has a genie inside, like

the sealed jar the fisherman found in the 'Arabian Nights'?" cried Sylvia.

"What fun if it had!"

"By genie, I presume you mean a Jinnee, which

is the more correct and scholarly term," said the Professor. "Female,

Jinneeyeh, and plural Jinn. No, I do not contemplate that as a probable

contingency. But it is not quite impossible that a vessel closed as Mr.

Ventimore describes may have been designed as a receptacle for papyri or other

records of archæological interest, which may be still in preservation. I should

recommend you, sir, to use the greatest precaution in removing the lid—don't

expose the documents, if any, too suddenly to the outer air, and it would be

better if you did not handle them yourself. I shall be rather curious to hear

whether it really does contain anything, and if so, what."

"I will open it as carefully as

possible," said Horace, "and whatever it may contain, you may rely

upon my letting you know at once."

He left shortly afterwards, encouraged by the

radiant trust in Sylvia's eyes, and thrilled by the secret pressure of her hand

at parting.

He had been amply repaid for all the hours he had

spent in the close sale-room. His luck had turned at last: he was going to

succeed; he felt it in the air, as if he were already fanned by Fortune's

pinions.

Still thinking of Sylvia, he let himself into the

semi-detached, old-fashioned house on the north side of Vincent Square, where

he had lodged for some years. It was nearly twelve o'clock, and his landlady,

Mrs. Rapkin, and her husband had already gone to bed.

Ventimore went up to his sitting-room, a

comfortable apartment with two long windows opening on to a trellised verandah

and balcony—a room which, as he had furnished and decorated it himself to suit

his own tastes, had none of the depressing ugliness of typical lodgings.

It was quite dark, for the season was too mild for

a fire, and he had to grope for the matches before he could light his lamp.

After he had done so and turned up the wicks, the first object he saw was the

bulbous, long-necked jar which he had bought that afternoon, and which now

stood on the stained boards near the mantelpiece. It had been delivered with

unusual promptitude!

Somehow he felt a sort of repulsion at the sight

of it. "It's a beastlier-looking object than I thought," he said to

himself disgustedly. "A chimney-pot would be about as decorative and

appropriate in my room. What a thundering ass I was to waste a guinea on it! I

wonder if there really is anything inside it. It is so infernally ugly that it

ought to be useful. The Professor seemed to fancy it might hold documents, and

he ought to know. Anyway, I'll find out before I turn in."

He grasped it by its long, thick neck, and tried

to twist the cap off; but it remained firm, which was not surprising, seeing

that it was thickly coated with a lava-like crust.

"I must get some of that off first, and then

try again," he decided; and after foraging downstairs, he returned with a

hammer and chisel, with which he chipped away the crust till the line of the

cap was revealed, and an uncouth metal knob that seemed to be a catch.

This he tapped sharply for some time, and again

attempted to wrench off the lid. Then he gripped the vessel between his knees

and put forth all his strength, while the bottle seemed to rock and heave under

him in sympathy. The cap was beginning to give way, very slightly; one last

wrench—and it came off in his hand with such suddenness that he was flung

violently backwards, and hit the back of his head smartly against an angle of

the wainscot.

He had a vague impression of the bottle lying on

its side, with dense volumes of hissing, black smoke pouring out of its mouth

and towering up in a gigantic column to the ceiling; he was conscious, too, of

a pungent and peculiarly overpowering perfume. "I've got hold of some sort

of infernal machine," he thought, "and I shall be all over the square

in less than a second!" And, just as he arrived at this cheerful conclusion,

he lost consciousness altogether.

He could not have been unconscious for more than a

few seconds, for when he opened his eyes the room was still thick with smoke,

through which he dimly discerned the figure of a stranger, who seemed of

abnormal and almost colossal height. But this must have been an optical

illusion caused by the magnifying effects of the smoke; for, as it cleared, his

visitor proved to be of no more than ordinary stature. He was elderly, and,

indeed, venerable of appearance, and wore an Eastern robe and head-dress of a

dark-green hue. He stood there with uplifted hands, uttering something in a

loud tone and a language unknown to Horace.

Ventimore, being still somewhat dazed, felt no

surprise at seeing him. Mrs. Rapkin must have let her second floor at last—to

some Oriental. He would have preferred an Englishman as a fellow-lodger, but

this foreigner must have noticed the smoke and rushed in to offer assistance,

which was both neighbourly and plucky of him.

"Awfully good of you to come in, sir,"

he said, as he scrambled to his feet. "I don't know what's happened

exactly, but there's no harm done. I'm only a trifle shaken, that's all. By the

way, I suppose you can speak English?"

"Assuredly I can speak so as to be understood

by all whom I address," answered the stranger.

"Dost thou not understand my speech?"

"Perfectly, now," said Horace. "But

you made a remark just now which I didn't follow—would you mind repeating

it?"

"I said: 'Repentance, O Prophet of God! I

will not return to the like conduct ever.'"

"Ah," said Horace. "I dare say you

were rather startled. So was I when I opened that bottle."

"Tell me—was it indeed thy hand that removed

the seal, O young man of kindness and good works?"

"I certainly did open it," said

Ventimore, "though I don't know where the kindness comes in—for I've no

notion what was inside the thing."

"I was inside it," said the stranger,

calmly.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)