Chapter Fifteen - The alarm of Kalulu’s friends—The search for Kalulu—O Kalulu, Kalulu!—Shall we never more see Kalulu?—Only trees, trees, trees—Kalulu is Lost!—The march to Unyanyembe—Why come ye in this guise, children?—Among friends at last!—Selim and Abdullah in Arab Costume—The Lion Lord’s City—Home again!—Selim embraces his Mother—Kalulu discovered!—The Slave-Market. How much for Kalulu?—Kalulu restored to his Friends—Kalulu introduced to Abdullah’s Mother—My Kalulu!

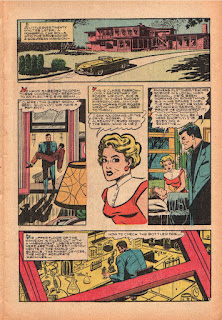

Returning to the camp of our friends, we find the sun has set, and darkness is settling fast over the earth. Simba stands at the gate of the camp with an anxious face, for his young friend Kalulu has not yet returned. Moto, Selim, and Abdullah are just within waiting, and listening eagerly for the slightest sound of footsteps.

“What can be the matter with the boy? Dost thou think he could get lost, Moto?” asked Simba.

“No; Kalulu could not lose himself if he tried. He has slain something, and is coming with a heavy load of meat, so as not to make two journeys. It takes the like of Kalulu to know how to kill game.”

“I wish he had not gone away,” said Selim, “because it would be a pity if he came to harm when we are so close to friends.”

“What harm can happen to him about here, except from a lion or a leopard? But if he met either beast I would set Kalulu against him. There are plenty of trees about here for him to climb up, and I should like to see the monkey that would excel him in climbing,” said Moto.

Still the night grew deeper and deeper, and the anxiety of the friends increased.

“What road did he take; dost thou know, Moto?” asked Simba.

“I think he took the Unyanyembe road; but he may have gone after something in the forest. If he saw any game he would not be likely to remain in the road. He would go after it, of course,” replied Moto.

“Well, I am going to look for him. Wilt thou come? The boys can keep a good fire up to let us know where the camp is,” said Simba.

“What a soft fellow thou art, Simba! Dost thou not know that in the night we can do nothing to hunt him up, when he may be anywhere but in the place where we are looking for him? If we had a gun we might signal him; but by going out in this darkness we would only tire ourselves to no purpose. If Kalulu has been taken too far away by following an antelope or something else, the boy has a thousand ways of passing the night. He could sleep in a tree-bough, in a hollow tree, or in the burrow of a wild boar, just as well as he could sleep in the camp. I am no hunter like Kalulu, yet I could do it, for I have been lost many times in the woods. What we must do, is to sleep in the camp to-night, and the first thing at daybreak we two shall go different roads, and wake all the country round with our cries.”

“Thou art wiser than I am, Moto, yet it is very hard. If any harm comes to him, I shall always accuse myself for a poor silly fellow who did not know how to take care of a boy. I am sorry I did not stop him, for something tells me harm has come to him. I would I knew where he was. I would soon see whether a good friend at his back could help him or not. We shall rest here until daybreak, and may Allah grant that we find him!”

“Amen, and amen,” responded the Arab boys fervently.

At break of day Simba woke his friends. He had not slept a wink, though he had lain down. With a heart that had palpitated violently at every sound, he had lain listening acutely to every noise that broke the silence. It might have been a light-footed antelope, or the rustling of a fan palm, or the fall of a branch, or the shuffling feet of a hyaena, yet each of these, as he heard it, had inspired a momentary hope that it was the footstep of the returning Kalulu.

Simba was impatient to be off and to use his strong lungs; and when the sun was up, he was brusque in speech to Moto, when he said:

“Come, man, art thou never going to stir? Let us be off. Which way wilt thou take, south or north?”

“Oh, any road will do for me; do thou take the south, I will walk towards the north, and let each of us strike towards the east. We must be back by noon, for if Kalulu is not here by then, and neither of us have found him, then he is—”

“What, Moto?” said Selim, now really alarmed. “Oh, do not say he is lost! We must find him. We cannot give him up. I will go along the Unyanyembe road as far as I can, and return here by noon.”

“Young master,” said Simba, “don’t go away from this camp, I beg of thee. To lose Kalulu is as much as I can bear; but if thou art lost too, then may all the bad things of this earth happen to me, I do not care how soon.”

“But, dear good Simba, it is now day. I cannot be lost, for I will not leave the road. Whilst thou and Moto go north and south, I will take the eastern road, and after going two hours on the road, I shall return along the road to the camp. Who knows what has happened to my brother Kalulu? He may be wounded, and I may find him waiting for us. He has done enough for me; I ought to risk something on my part for him. I shall go, Simba—there. Abdullah and Niani shall stay in the camp to watch.”

“Well, well, as thou wilt. Thou art master here, and wherever I be. Come, Moto, let us be off.”

“Now, Simba,” said Selim, running up to him, “thou art angry with me. Seest thou not it is but my duty to search for him? Is it nothing, what Kalulu has done for me all these months? Be good, Simba, as thou hast always been to me. Let me go without feeling that thou art offended with me.”

“Nay, go, my young master, and Allah go with thee. Simba knows not much about Allah; but Simba, while he looks for Kalulu, will pray to him to be kind to thee, and look after thy safety. Come, Moto, let us go.”

“God be with thee, Simba, and with thee, Moto,” cried Selim, as he turned to depart.

“And with thee also,” replied Simba and Moto, as they strode off in their several directions.

Soon Abdullah and Niani, left alone in the camp, heard the shouts at intervals of each of their friends as they wandered off—

“Kalulu! O Kalu-lu! Ka-luuu-luu!” was the cry they heard repeated until the sounds were lost by distance.

Selim strode on, uttering the name of his lost friend over and over. He made the thin forest ring with its liquid sounds until he fancied that every tree lent its aid to cry out the sweet name.

“O Kalulu—Kalulu—Ka-luu-luu-u!” was uttered on the desolate plain among the dwarf ebony and blue gum. The thick forest beyond was reached, and here again the stunted woods re-echoed to the name of “Kalulu.” There was no reply. There was not the slightest trace of any Kalulu in the grim solitude. The forest was as calm and silent as though no one had ever ventured within its gloom since it grew. He looked down on the road; the road was smooth and compact, though now and then he thought he saw traces of human toes; but there were so many of them, one person could never have made so many marks with the toes of his feet. Was it not the road on which caravans journeyed to Unyanyembe?

After he had gone many miles through the forest, Selim began to retrace his steps towards the camp, but still shouting the beloved name of “Kalulu;” but there was no reply to it, and sorrow, alarm, and gloom settled down on his heart, and in this state he reached the camp, a little before noon, to wait the arrival of Simba and Moto.

His friends soon returned, as unsuccessful as he, without having seen the slightest trace of him whom they now began to lament as a lost friend.

The sorrows of Kalulu’s friends were deep. Selim wept copious tears, and all his imagination could not lighten the gloom he felt over the fate of his friend and adopted brother, who had been so good to him; no fancy could alleviate for one instant the overwhelming misery that the unexplained absence of Kalulu now caused. Continually he asked himself what could have befallen him, but all in vain. He had gone away in the full vigour of his youth; his lithe, slender, but sinewy form seemed so indurated and so protected against all mischances by the clever head to plan, the muscular arm to execute, and the clean-shaped limbs and swift feet to run, that he appeared invulnerable. And he had gone away smiling, but since then there was no clue, and his imagination and fancy were paralysed.

Selim turned to Moto, and asked:

“Oh, if thou canst give me the slightest hope that I shall see Kalulu again, I will bless thee?”

“I can’t think of anything. A lion may have followed him and sprang on him, and carried him away bodily—though it is unlikely. A buffalo may have gored him, and left him dead. Savage men may have found him and made him a captive; though as this is a ‘polini’ (a wilderness) I don’t see how men could be here. Thou knowest what he has done already, how quick and cunning he was with his arm and feet. He was a true son of the forest; and if danger and death overtook him, it must have been very sudden.”

“What dost thou think, Simba?” asked Selim.

“I can’t think of anything, young master, except that he is not here, and we don’t know what has become of the brave young chief without whose aid none of us would have been so far on our way home;” and the generous-hearted man wept aloud, and his weeping had a sad effect on all.

“And shall we see—never more see Kalulu?” sobbed Abdullah; “never more see him who saved me from the jaws of the monster in the Liemba, who freed us from bondage, who was our friend and brother, who has been everything to us, the kindest, best, the noblest Pagan child that ever breathed?”

“He who saved me from death in the forest, who made me his brother, and stood by me through many troubles—who on my account threatened Ferodia, and from that lost his kingdom—with whom I have roamed through plain and forest, and have talked so often with as a brother—the dearest and best brother I can ever have!” cried Selim.

“Stay, young masters, do not give way to such tears. Kalulu may not be lost. He may return to the camp this afternoon. I am going out now to look for him again, and to see if I cannot get something for us to eat,” cried Moto. “Meantime, hope; stranger things than his return have happened.”

The boys and Simba looked their gratitude, as, next to Kalulu, they knew that Moto was the best woodsman of the party. Moto strode off in the direction of the Unyanyembe road.

At night he returned, bringing on his back a fat young antelope, and news which made all start.

Said he, while he and Simba turned to prepare some of the meat: “I went along the same road that master Selim went this morning. I crossed a ‘mbuga’ (small plain), and came to a thick forest. Soon after entering the wood I saw on the left-hand side of the road a yellow heap of earth which a wild boar had made above his burrow. I went up to it, and what do ye think I saw?—the marks of two feet of a boy. They were small and narrow, not broad and large, like a man’s foot—Simba’s or mine—would be. They must have been Kalulu’s. He had jumped on that yellow mound, for the toes had sunk deeper in than the heels. I went on, where the leaves had been disturbed, but all marks were soon lost. However, I went further on in that direction, and in about half an hour I came to a camp, not fenced round, but where fires had been kindled. The ashes below the surface were slightly warm. If Kalulu is anywhere, I feel sure that Kalulu is with those people. But who are those people? Are they Waruga-ruga (bandits)? Are they Wanyamwezi? Are they natives? Are they Arabs? This is a ‘polini’ (wilderness); there is no village near here. Where have those people gone to?”

“Let us go on, then, and find out; let us follow this road until we come to some village where we can ask?” said Simba.

“Yes, yes,” said Selim, “let us go.”

“I am ready now,” said Abdullah.

“Wait, young master, and thou, Simba. Eat first as much as ye can, then we can go,” said Moto, in the tone of one who knew what he was about.

In an hour a full meal had been despatched, and about an hour before sunset they started towards Unyanyembe; but before they reached the camp which had excited Moto’s attention it was dark, and prudence insisted on them stopping there.

All kinds of suggestions were made as to Kalulu’s fate, and they fondly called up, by retrospective glances at the past few months, all they knew concerning Kalulu, all he had done, his amiability, his kindness of heart, and the generous character of the young chief, until each sighed for morning.

There was but little sleep that night, and the next morning they were early afoot on the road. The narrow path which they trod led to Unyanyembe, and had been tramped to hardness and compactness. It ran around bushes; sometimes it went straight ahead; then it made great curves like a lengthy brown serpent. There seemed no end to the road or to the forest. It was ever woods, woods, woods, in their front—woods to the right of them, woods to the left of them, woods behind them, and not a sign of cultivation or of population anywhere. Only trees, trees, trees. Trees of all kinds—the candelabra kolqual, the prickly cactus, spear-leafed aloes, thorn-bushes, gummy woods, silk-cotton trees, sycamores, mimosa, plane, or the silvery chenar, tamarinds, wild fruit-trees, but no fields or villages.

Darkness coming on at fall of day, they sought a place to make their camp.

Another day dawned, and again they were on the road; the forest thinned into park-land—the park-land gave place to a sterile bit of chalky-coloured plain—the plain was succeeded by a thin forest—the thin forest by a jungle—the jungle by a plain again, and still there was no sign of living man or of men. They seemed to be the only inhabitants living in the world. Yet the road still ran before them in serpentine curves and long, straight stretches.

At night they rested again near a broad river. They were eking out their meat as much as they could, and at dawn they continued their march. At noon they saw fields of young corn, and beyond the yellow tops a village, and when they came to it they saw natives standing outside the gate.

“Ho, my brothers, health to ye!” cried Moto.

“Health, health to ye!” was the response.

“What country is this?”

“Manyara.”

“Manyara!” cried Moto, astonished.

“Yes, and Ma-Manyara is king.”

“Why, then, Unyanyembe is not far from here?”

“About nine days off.”

“Was not that the Gombe River we passed?”

“Yes, if you came from Ukonongo along the road.”

“We did. We have been hunting, and have had a misfortune on the road. We are going to Unyanyembe. What news?”

“Ah! Good news. Manwa Para is dead.”

“Dead, is he? Have ye seen a caravan lately going by here towards Unyanyembe?”

“No—none for many days.”

“Health, health to ye, my friends!”

“Health, health!” was the response.

Our friends strode on until they got beyond the cultivation and were deep in the forest again, when Moto turned round and said:

“Kalulu is lost!”

“Lost! Oh, Moto! must we give him up for ever?” asked Selim.

“I fear so. I thought that caravan belonged to Arabs. If they were Arabs they would have come this way, and those people at the gate would have seen them. But I think now that camp belonged to the Waruga-ruga (bandits). And where have they gone to? Are they from Ugala or Ukonongo? Were those people Wazavila or wild Wanyamwezi? They were not Arabs, or they would have come this way. We are too far away to go back, and we might hunt for Kalulu years and years among the tribes about here without finding him. The bandits kill all men as soon as they catch them, if they cannot make slaves of them. They are never seen. They are everywhere, but nowhere when ye desire to see them. No; Kalulu is lost, and unless we want to lose ourselves, we must go on to Unyanyembe.”

This was a sudden shock to the Arab boys and to Simba. They had nourished a lively hope that their friend might be found, but they were now sternly told that their friend was “lost.”

“Poor Kalulu!” said Selim. “He is not lost to me. I will build him up—from his feet to his head, with all his fine high courage, quick, generous temper, and his warm heart, in my memory, where he shall dwell as the noblest and best I have ever met. Until I die I shall remember him as the truest friend and kindest brother.”

“And so shall I, Selim,” said Abdullah. “Thou and I shall often talk of him as one to whom there was no equal in worth. When we meet our mothers, we shall remember his name as one without whom they never would have seen us again, and our mothers shall bless him. His memory shall be to me like a plant nightly watered by the dew of heaven, never to die, and whenever I hear his name mentioned I will pray that I may be like him. For Kalulu’s sake, all black people who call me master shall be well treated, and shall never be abused.” As he said these words, little Abdullah wept copiously, as the worth of his friend rose so vividly before him.

“And I make a vow,” said Selim, “for my brother’s sake, never to purchase a slave for my service while I live; and when I die my slaves shall all be free. No black man in my service shall have cause to regret that I met with Kalulu in Africa; but they shall rejoice, and know that their treatment is due to Kalulu alone, that they may sing his praises under my palms and mangoes.”

“Allah be with ye both!” cried Simba. “If all Arabs were like ye, the Arab name would become beloved throughout all the tribes of the Washensi.” (Pagans.)

“Ay, so it would,” said Moto; “so it would; and the people of our race and colour would not be bought like sheep and goats, and driven with sticks to the market to be sold. A great wrong is done by the Arabs every day in this country, and it is no wonder that the tribes treat them badly when they can. Tifum treated Masters Selim and Abdullah cruelly, because he heard that they did the some to the black people. We, thou, and I, Simba, should not have been so good as we are had any other than Sheikh Amer bin Osman been our master.”

“I believe thee, Moto,” replied Simba. “We would not be going back to Zanzibar either, if noble Amer’s son was other than he is. Master Selim is the best Arab living. Prince Madjid’s sons are worthless, compared to my young master. But let us go to Unyanyembe, before some evil overtakes Selim and Abdullah, and we have no hope of pleasure left to us more.”

Moto started at the suggestion of evil to his young master, and at once put his best foot forward, until they came to a plain, where he strove to obtain an additional supply of meat, and was so successful with his arrows, that he brought down a zebra.

The march to Unyanyembe lasted fifteen days longer, owing to the lack of the cheery presence of Kalulu, and to the frequent stoppages they had to make to procure food, and to nourish their strength; but on the morning of the sixteenth day, the well-known features of the hills around the Arab settlements greeted the eyes of Moto and Simba, who had seen them before. To their left rose the table hill of Zimbili, at their base were the Arab houses of Maroro, and stretching nearer to them, was the fertile basin of Kwihara; and soon rose before them the Arab houses of Sayd bin Salim, Abdullah bin Sayd, Sheikh Nasib, and of the redoubtable Kisesa. But passing by these, and walking rapidly along a road which led through Kisiwani, and between two hills which separate Kwihara from the larger settlement of the Arabs, the great tembes of Tabora greeted them, each surrounded by plantains and pomegranate trees.

Upon asking some of the people who were passing from Tabora to Kwihara—and who stared at Selim and Abdullah as if they had never seen Arabs before—who lived at Tabora, they were given a long list of names, and among these was the name of Sultan bin Ali!

“Where does he live?” asked Selim.

“Yonder, by that big tree. The first tembe ye come to.”

Selim and Abdullah gave a shout of joy, in which they were joined by Moto, Simba, and Niani, and as they passed on, Selim proposed that they should break in upon the old man suddenly, who would no doubt be found on his verandah, chatting with half-a-dozen other Arabs.

In a few minutes—minutes that were never counted, but which glided by swiftly—they found themselves pushing their way through crowds of well-dressed Zanzibar slaves, who looked upon the Arab boys with surprise, mingled with awe, but who made way for them immediately, but eyeing them as if they had never seen Arabs.

Selim and Abdullah passed on, however, and came at last before the spacious tembe. They saw the white-bearded Sheikh, seated with his back to the wall, leaning on a pillow which was covered with gay print. On each side of him sat several other Arabs. All started up as they saw the strange Arab boys, undressed and naked, with the exception of ragged pieces of dirty cloth about their loins, walk up to them, and heard the unmistakable Arabic of Muscat, as the boys said:

“Salaam Aleekum!” (Peace be to ye.)

“Aleekum Salaam!” (and unto ye be peace), responded the startled Arabs, rising to their feet.

“Are ye Arabs, children?” said the old Sultan bin Ali, gazing at them sternly.

“We are children of the Arabs of Muscat,” answered Selim, with a tremulous voice.

“How is it, then, in the name of Allah,” said the aged Sheikh, “that ye come in this guise, naked, into the presence of true believers?”

“Our fathers are dead. They were rich merchants of Zanzibar. They were slain in battle, and we, their sons, were made slaves. After many months we have escaped—praised be Allah for his mercies!—and have sought ye, our kinsmen.”

“Slain in battle!” echoed the Sheikh. “Who are ye? In what battle were your fathers slain?”

“This,” said Selim, pointing to Abdullah, “is Abdullah, son of Sheikh Mohammed bin Mussoud; I am Selim, son of Amer, son of Osman; thou art Sultan, the son of Ali, my kinsman and friend.”

“Oh, blessed be the compassionate God! Praised be the Lord of all creatures—the most merciful, the King of the Judgment-day!” cried the aged Sultan, as he rushed to Selim and Abdullah, and brought them together, and embraced them both at once, and kissed their foreheads, and would not release them for a moment, but continued to pour his kisses on their faces, and endearing terms into their ears, while hot tears poured down his cheeks as he said, looking at them with a memory which carried him and them to that fatal day in Urori, “And thou art Selim, the son of noble Amor, my kinsman! and this is Abdullah, son of Mohammed! Ah, wondrous are the ways of God, and merciful is He to true believers! I see Amer and Mohammed in your eyes, children; how came I to forget that fatal day of Kwikuru? But enter, children. Enter, in the name of the Most High. Amer’s kinsman cannot forget his duties to Amer’s son!”

But the other Arabs could not permit Sultan, son of Ali, to take the boys away without being permitted to embrace them, and while scalding tears fell down their cheeks, they cried out, “Blessed is the Most High, the merciful and compassionate God!” and poured their congratulations into the ears of the escaped captives.

Before quite going in at the door of the tembe, Selim turned to Sheikh Sultan and said:

“Sultan, son of Ali, let not the son of Amer be called ungrateful. Lo! here are my friends. Thou hast not thanked them for what they have done to us. This is Simba, and this is Moto! Dost thou not know them?”

“Ah, who does not know Simba and Moto?” said the old man, as he rushed at them and gave them a warm embrace, and kissed, out of pure gratitude, those rugged and dusky men of Africa. “Enter, men, in the name of God. Command the kinsman of Amer, what ye will eat, and drink. But who is this little fellow—thy son, Simba?”

“No, Sheikh Sultan; he is Niani, Master Amer’s slave.”

“Is he the little fellow who used to play tricks upon Isa, son of Thani, Selim?”

“The same.”

“Come, child, to an old man’s arms!” said he, as he caught him up, and gave him a warm kiss.

Simba, and Moto, and Niani found themselves embraced by the other Arabs in turn, and Sultan bin Ali’s slaves, hearing who they were, came rushing up by the dozen to embrace their friends, whom they had given up as lost for ever, on that fearful day, when four hundred Arabs and their people met with such a sad fate.

But Sultan bin Ali, seeing them thus engaged, turned to his slaves, and bade them prepare the best at once for food, and then ushered Selim and Abdullah to his own cosy, carpeted room, and, inviting them to rest a moment, hastened out again to an Arab of middle age, named Soud bin Sayd, who was seated on his verandah, and said to him:

“Soud bin Sayd, thou hast two sons of the same age as these boys. Hasten, my friend, bring two dresses for these children—the best thou hast—name thy price for them, but bring them.”

“Do not name price. Sheikh, thou hast them. I will but mount thy riding-ass and be back before thou canst say, Bismillah!” and the good-hearted man hurried off as he said it.

Then Sultan bin Ali called to his barber, and bade him bring his basin and razors directly to him, then joined the young. Arab boys, who had been weeping continually for joy, fast locked in each other’s arms.

The barber soon came, and Sultan told him to shave off the boys’ hair, which was grown almost to their shoulders. Before the depilatory process was completed, Soud bin Sayd had returned with two complete dresses—shirts, handsome embroidered dishdashehs (robe), and embroidered skull-caps, two fine blue cloth dämirs (jackets), wide-flowing linen drawers, and slippers.

Then, excusing the barber of the kind-hearted Soud, Sultan ushered the boys into the lavatory with their new dresses, where there was abundance of water, soap, and towels for them; and after telling them, when dressed, to come out to him and his friends on the verandah, he closed the door on them, and joined the Arabs, who were still in a high state of excitement, consequent upon the unexpected appearance of the Arab boys, and their marvellous escape from slavery.

“Sultan, son of Ali,” said Soud bin Sayd, “this is a great day.”

“Thou mayst well say so. How rejoiced the widows of Amer and Mohammed will be, and Leila, who is to be Selim’s wife when he gets old enough! My friends, ye must join me in eating the noon-day meal with the poor children, that they may feel that they are among kinsmen and friends once more. Poor boys! what they must have suffered! But there is a great deal to be told yet; we shall hear their story presently. I am glad ye are here to welcome them with me.”

“It is wonderful!—wonderful! I feel impatient to hear all they have to say,” said a swarthy-faced young Arab of about twenty-five.

Within half-an-hour the two Arab boys, Selim and Abdullah, came from their room, dressed, and so changed they could barely be recognised as the wild-looking, long-haired boys who had so electrified the old man with their unpresentable appearance. Selim came first, Abdullah behind, the Arabs rising respectfully as they came near, the former advancing to Sheikh Sultan, with his handsome face all aglow at the change he felt in him, took hold of the old man’s right hand, and raised it respectfully to his lips, and went on to the other Arabs to do the same to them, but they would not permit this, but saluted him on the cheek, as well as Abdullah.

The Sultan bin Ali invited the boys to the seat of honour near him, and had pillows brought for them, so they would not feel chilled by contact with the wall, and invited Selim to tell his story, with which he at once complied, and gave them a succinct but brief account of all that happened to them from the battle-day to their appearance at Unyanyembe. He never had such an attentive audience before in his life. The Arabs were deeply interested in it, and often broke out into exclamations, which showed the two Arab boys that they were really amongst friends at last. Kalulu received great praise, and Sultan bin Ali expressed his fears that the boy was either murdered or carried into hopeless captivity and slavery.

Presently food was brought in such quantities that made the hungry boys stare; one dish was expressly for Simba, Moto, and Niani, who were called from among their friends to partake of it. Water was poured over each person’s right hand, and as Selim and Abdullah saw the great dish of snowy rice, and the dish of curried meat, they could not help uttering one great long sigh of satisfaction. Sultan assisted the boys to the best portions, placed more curry over their rice than he placed over any other, though he did not neglect his guests. Then hulwa (sweetmeats) and sweet cakes were brought, with honey, and the boys were continually urged to eat, until they at last declared that they had had enough.

The next day the two Arab boys were taken to all the tembes of Tabora, Kwihara, and Maroro, where they were heartily received by everybody, and were invited to feasts, which followed one another in quick succession, until, at the end of a month, Selim and Abdullah had fed so well that they got quite rotund in figure, and appeared none the worse for their privations.

After two months’ stay at Unyanyembe, Selim and Abdullah were placed in charge of Soud bin Sayd, who was bound for the coast with a caravan consisting of two hundred slaves, loaded with ivory. Sultan bin Ali and a dozen other Arabs accompanied Selim and Abdullah as far as Kwikuru, three miles from Tabora, and after fervently blessing them, and wishing them all sorts of success, and a long-lived happiness, parted from them with saddened faces.

Tura, on the frontier of Unyamwezi, was reached within five days, and crossing the wilderness of Tura they merged in New Ukimbu. Within three weeks afterwards they were travelling through arid Ugogo, which they passed safely in two weeks; then the friendly wilderness of the Bitter Water—Marenga M’kali—burst upon their view, and the next day, after a march of thirty miles, they were defiling by the cones of Usagara.

Continuing their march, ten days more brought them to the Makata Plain, and on the eighth day after leaving Usagara they camped near Simbamwenni, or the “Lion Lord’s” city, which both Selim and Abdullah remembered as the scene where Niani had a disagreeable incident with Isa. Poor Isa! he is dead.

After a rest of two days at Simbamwenni, the caravan of Soud bin Sayd continued its march, and on the seventieth day from Unyanyembe the Arab boys, Selim and Abdullah, and their friends, Simba, Moto, and Niani, looked at the sea of Zanj, from the ridges behind Bagamoyo, and pointed out its ever-smiling azure face to one another with emotions too great for utterance. They feasted their eyes on it until they lost sight of it, as they plunged into the depths of the umbrageous groves and gardens of the sea-coast town of Bagamoyo, into the streets of which they presently emerged, to be welcomed, as wanderers generally are, with glad cries, embraces, smiling countenances, and hearty claspings of the hand.

The next day Soud bin Sayd embarked his caravan in two Arab ships, and accompanied by the young Arabs and their friends he had the anchor hoisted, and the lateen sails sheeted home, and the ships began to move, as they felt the influence of the continental breeze, towards Zanzibar, across the strait which separates Zanzibar from the mainland.

“Moving towards home!—glorious thought!” cried the enraptured Selim, as he turned towards his friend Abdullah, and fell on his neck overpowered by his feelings.

“Home!” said Abdullah, “at last! We have been frequently tried, Selim, but we have been taught good lessons. Thanks be to Allah! He has been but trying us, to make us better and purer, and I mean to profit by what I have learned. Wilt thou, Selim?”

“With the help of God, I will,” he replied.

“Dost thou know what chapter of the Küran fits our case better than any other, Selim?” asked Abdullah.

“Which?”

“That entitled the Brightness, wherein the Prophet, blessed be his name! says: ‘By the sun in his meridian splendour, by the shades of night, thy Lord hath not forsaken thee, neither doth He hate thee. Did He not find thee an orphan, and did He not take care of thee? And did He not find thee wandering in error, and hath He not guided thee into the truth? And did He not find thee needy, and hath He not enriched thee? Wherefore oppress not the orphan, nor repulse the beggar, but declare the goodness of thy Lord.’”

“Beautiful!” said Selim; “oppress not the orphan may mean oppress not the slave. He found us fatherless, and He took care of us. He found us needy, ailing, perishing in the wilderness, and He hath enriched us. Praised be God, the one God, the eternal God, He begetteth not, neither is He begotten; and there is not any one like Him.”

“Amen! and Amen!” responded Abdullah. “There is only one God, who is God, and Mohammed is His Prophet.”

“Amen! and Amen!” exclaimed Simba and Moto, who were as powerfully affected by their present and coming happiness as were either Selim or Abdullah.

The shores of Zanzibar at last were seen to rise from the sea, like an emerald set in the centre of a circular sapphire, and the lovely isle was hailed by vociferous shouts by the wanderers, while their hearts beat faster and faster. They neared the shore steadily, and each point became an object of interest, and every well-remembered house received due attention. Finally, the ships rode in the harbour, and Selim, and Abdullah, and their friends, bidding a kindly farewell to Soud bin Sayd, after inviting him to come and see them, got into a boat called by the kind Arab, and were rowed ashore.

As they stand at last on the island where both of these boys were born, on the threshold of their own homes, how much money would, we wonder, induce them to return to Africa without ever having seen their homes? Judging from their faces, we should think the world would not be sufficient, not even to induce them to return to Bagamoyo. What bright, joyous faces they wore! What flashing eyes! Men turned round in the streets to look at them, and talked to their companions, with smiles, about their looks. They saw several whom they knew, but they were too impatient, so near home, to stop to talk to any one, and they paced determinedly towards home; they passed the Arab, the Hindoo, the Negro quarter; crossed the bridge, and were among the gardens of the rich Arabs. Once outside the city, the capital of the island, they broke into a run; but as they drew near their homes they sobered down, became exceedingly agitated, and pale in the face.

Abdullah suddenly shouted, “There, Selim, is my home! As thou hast to pass it, come with me.”

Selim consented, and accompanied his friend to the door, gave him one last embrace, bade him come round and see him soon; and then bounded off towards his own stately mansion, accompanied by Simba, Moto, and Niani.

He saw the mangoe trees, the orange-groves, the cinnamon and the slender clove trees. Soon he saw the house itself, looming large and white between the trees; he saw the latticed windows, which he had often pictured to himself in the depths of the African wilderness; he saw the cupola of the Arab temple, which his father, Amer, had erected; he saw the walls of the courtyard; he cast one glance at the blue sea, and the spot consecrated by happy associations, where his father and kinsmen had often sat, gazing upon the sea; and then burst through the door of the courtyard, dashed breathlessly across it, and through the great carved door of the mansion, up the stairs, and into the harem, where he saw a woman seated on the divan, near the lattice, looking out. One penetrating glance assured him that she was Amina, his mother! She looked up and saw her son, Selim! returned to her heart and love! from Negro-land.

Let us drop a kindly veil over the solemn and affecting meeting of mother and son, feeling assured that the joy of both was indescribable; that they interchanged the most endearing phrases; that they embraced each other as loving mother and loving son, long parted, would; that while he sat by her side he poured into her ears the sad tale of woe, bereavement, suffering, privation, difficulty, disappointment; the account of the marvellous adventures, hair-breadth escapes; of true friendships formed; the sacrifice, the courage, and the constancy of one whom he could never forget, Kalulu; and that his mother gave him an account of all that she had endured for the last two years; how his uncle had attempted to manage the estate himself, but she would not permit him, knowing his character; how everything had prospered during his absence; how rich he was; and how, with Leila’s portion, which Khamis, her father, had given her, he might consider himself one of the richest men on Zanzibar Island. But she begged of him not to think of marrying yet, as he was not yet eighteen—a mere boy—to which Selim gave his promise.

What wonderful things they had to tell each other! things which do not concern the world to know, but concerned both mother and son; which they appreciated, and enjoyed, and could repeat, and laugh merrily over together, without caring one jot what the world outside thought.

On the third day after his arrival at Zanzibar Selim, accompanied by his factor, a smart, shrewd, clever, honest Hindoo Mahometan, by Simba, Moto, and Niani, went towards the city to purchase clothes for his faithful servants and their families. On the way he turned to Abdullah’s home and called out to him to ask if he would like to go with him. Abdullah was only too happy, and forthwith appeared outside, dressed in the very height of Arab fashion, and as gay as could be.

Arriving within the city, the factor drew for Selim’s use the sum of two hundred dollars, and then, before making any purchases, Selim called upon the sons of the Zanzibar Sultan, his old playmates, who warmly greeted him, and who detained him to hear his story about his sufferings and escape from slavery, all of which the factor had already known from Selim and his mother. Several other friends living in the neighbourhood of the Sultan’s palace, were called upon, all of whom expressed the greatest surprise and pleasure at seeing him.

Selim, accompanied by his friends, was about crossing to Shangani Point, when they suddenly came upon the slave-market, crowded with the miserable beings about to be offered to the highest bidders. The buyers were there in considerable numbers, stout, portly Arabs, and well-to-do half-castes, besides Mohammedans from India, who bought for other people, all of whom were examining critically the subjects to be sold. These “subjects” were of all ages, and of both sexes, almost entirely nude. Hardly one of them had a healthy look, mostly all appeared half-starved and sick. There had lately been several importations from Kilwa, Mombasah, Whinde, Saadani, and Bagamoyo, which had eluded the searching eyes of the British cruisers and the agents of the British consulate. But here they were almost under the windows of the house over which the flag of England waved, examples of human suffering, subjects of human brutality; the most hapless-looking beings, the most woe-begone “human cattle” that the sun had ever shone upon.

Selim was about departing, disgusted with the brutal scene, when, casting a last look at the auctioneer, he saw the face of the slave whom he was about to sell. With a frenzied look and pale face he said to the factor, to Abdullah, and his other friends:

“Come this way—come this way—quick, for Allah’s sake,” drawing the factor away after him until he was hidden from the auctioneer’s gaze behind a group of sightseers.

“What is the matter, Selim?” asked Abdullah. “Art thou sick?”

“Sick! No; but listen all of ye. Do ye see yon slave about to be sold now?”

“Yes,” answered all.

“Then that slave, as sure as Allah is in heaven, is my adopted brother Kalulu!”

“Kalulu!” exclaimed the startled friends. “Yes, Kalulu!”

“Wallahi, he is!” exclaimed Moto in an excited tone. “There is not another here present who can hold his head like that, be he Arab or African. He is the King of the Watuta! I swear it;” and as he said that he was about to rush off, followed by Simba, when Selim shouted, “For Allah’s sake, don’t stir!”

“Why? He is not a slave,” shouted Simba. “He has been stolen by that Arab caravan, which travelled by night, because the chiefs feared the day, bike thieves. Moto, thou wert right. I see it all now. Wallahi! but I will break the back of the thief, even if the Sultan of Zanzibar cuts my head off. Let me go, Selim!”

“Silence, Simba,” said the factor. “Thou wilt draw attention to the young master. I see what Selim wants. He wants me to go and buy him. Ah, ha! Africa has taught thee cunning, Selim!”

“Yes, go,” said Selim. “Offer anything; but don’t let him be bought by anybody else. Give a thousand dollars for him, but bring him to me. We will wait thee here.”

“Fear not; but there is one thing thou hast not observed, Selim. I know I shall get him cheap. Dost thou not see that he is handcuffed? He is dangerous. Simba, be thou ready. Watch me nod my head, do not stir until I do so, then go to him and catch him. When I have paid the money he becomes Master Selim’s slave. And thou, Selim, keep guard over this big fellow, or he will ruin the game I am going to play. Abdullah, Moto, do ye hear?” asked the factor.

“We do; we understand,” they answered.

From their position they could observe everything without being seen. They saw the factor make his way to the front among the buyers. They heard the auctioneer, a sturdy, strong-voiced fellow, conspicuous from an enormous turban he wore round his head, bellow out:

“Ho, Arabs, children of Zanzibar, and ye rich men, look up! Here is a priceless slave from Ututa. He calls himself King of Ututa” (a laugh from a bystander). “Kings command high prices.” (“They make very bad slaves!” shouted Selim’s factor.) “I am going to run this fellow high.” (“No you won’t;” Selim’s factor.) “Look at him well. Watch his eyes; they are living fire. See the pose of his head. Observe his limbs; clean and well-shaped as a Nedjèd mare’s. Look at his chest; there’s wind, there’s hard work there.” (“Very little work, plenty of wind to run;” Selim’s factor.) “Just take a glance at his teeth; there,—open boy. No, dog! take that” (buffeting him). “Look at his hair; it hangs below the shoulders. Believe me, no slave was ever offered in this market to equal him. Offer; an offer, Arabs. Rich men, who require a good slave, make an offer for the best slave ever brought to Zanzibar.”

“Say, auctioneer, why is he handcuffed? did he try to murder his master? And why is the chain about his neck? Has he tried to run away?” asked Selim’s factor.

“Silence!” thundered the auctioneer. “An offer is what I want.”

“Two dollars!” shouted the factor, smiling sardonically.

“Two dollars!! Only two dollars! for this unequalled slave. Man, look at him, and offer a hundred.”

“Five dollars!” shouted a bystander.

“Five dollars! Five, five, five, five, five.”

“Six!” shouted the factor.

“Six dollars! Six, six.”

“Ten dollars!” from a bystander.

“Twenty dollars!” shouted the factor.

“Twenty dollars. Come, bid up. Only twenty, twenty, twenty, twenty. Who goes beyond twenty?”

“Twenty-five!” shouted the bystander.

“Thirty dollars! He is worth more, but he is a devil. I can see that by his eye.”

“Thirty, thirty, thirty, thirty. Bid up. Only thirty! He is worth more. Bid up, Arabs. Thirty, thirty, thirty. Going,—going,—going,—gone!” and the auctioneer nodded to the factor.

The factor walked up, counted thirty dollars in American gold to the auctioneer, who laughed as he put the money in his pouch, and said:

“My friend, this slave will murder thee the first time he catches thee asleep. Be wary of him; I should hate to hear some morning that thy throat is cut from ear to ear.” ear.

“Fear not for me, my friend. I have seen worse than he is tamed. Release his neck from the chain. Let go his hands.”

“Art thou mad?” asked the auctioneer.

“Not at all. Let him go free,” replied the factor.

The neck-chain slipped off, and the hands were about to be freed, when the factor nodded to Simba, who sprang through the bystanders like a very lion, and while the hands were being freed, uttered, with his deep voice, the magic name—

“Kalulu!”

The slave, still on the stand, turned round at the sound of the word. He saw the unmistakable face of Simba, and behind him, advancing slowly, two Arab boys, well-dressed, whom he did not know, but he recognised Moto and Niani. He reeled as one struck, but the great strong arms of Simba were round him; they lifted him up from the stand, carried him on the run towards the two Arab boys, and he was placed face to face with the tallest of them.

“See, Kalulu, dost thou not know Selim?” asked Simba.

The astonished boy looked at the face one moment. He saw him advance—with his old smile towards him, and he sprang at him, and thus it was how the two friends had met after so many months. Abdullah, Simba, Moto, Niani, were embraced one after another, to the astonishment of the bystanders, who could not conceive how such Arab boys could degrade themselves so low as to hug a slave that a few minutes ago was in chains, and sold for the cheap sum of thirty dollars!

Are not all bystanders in all parts of the world always wondering why such and such things happen? Is not the world for ever in a maze, and deeming many things of like nature to be incomprehensible? When was the world not shocked at an exhibition of nature?

But our friends paid no heed to the surprise of the bystanders or to their remarks; they left the marketplace arm in arm, and proceeded towards a shop where “long clothes” were sold. An Arab shirt thrown over him, and a piece of white cloth folded around his head, made a wonderful change in Kalulu. Then Selim gave orders to the factor to purchase the best clothes he could get for Kalulu, blue cloth jacket, embroidered cap, and embroidered shirt, linen drawers, crimson fez with long blue tassel, and slippers, besides a Muscat shash and Arab dagger, over and above what he had intended to purchase for him, to which the factor promised to pay implicit attention.

Selim turned to Kalulu and said:

“In two or three days, Kalulu, thou wilt be as well-dressed as any son of an Arab in Zanzibar; but now I must show thee my mother and my home. When we are outside the city thou canst tell us thy story.”

In half an hour they were in the country; and Kalulu, when requested to begin, said:

“I went out to look for game, and coming to the forest I saw smoke, and men wearing Arab clothes. I went to their camp when I found they were Arabs, not thinking they could act as they did. They spoke me fair at first; but while I was seated alongside of the chief his men sprang on me, and they chained me. I struggled hard at first, but they hurt me and abused me as if they meant to kill me. We travelled that night through the forest, and every night until we came to Unyanyembe, where we were kept in a house in a dark room. After a few days we began another journey, which ended at this sea. On coming to the island the chief put me to work in the field; but they could not get me to work. They beat and beat me every day; but I would not work, and the chief, finding he could do nothing with me, sent me with many more to be sold. That is the story.”

“Dost thou know that thou art my slave now, Kalulu? But when I was a slave of thine thou didst set me free and protect me by making me thy brother. I do the same to thee now. Thou art free, and I shall be a brother to thee, and my mother shall be thy mother,” said Selim.

“And mine too, Kalulu,” said Abdullah; “Selim shall not keep thee all to himself. My mother wants to see thee. And here we are at my mother’s house, to which I ask thee to come now.”

In a few moments they were at the door, and Abdullah invited Selim and Kalulu to walk in. They were led up a flight of stairs, and presently stood in an ante-chamber. Leaving their slippers outside, Abdullah ushered his two friends into a spacious saloon, close to the walls of which ran a luxurious divan, covered with soft silken carpeting, the like of which Kalulu had never dreamed of before; the floor was also covered with Persian carpets of great thickness.

“Ah, Kalulu, my house is not so grand as Selim’s; but it is better than most Arab houses,” said Abdullah. “Stay here a moment until I go to prepare my mother.”

Abdullah was not gone long before he returned with his mother, whose face was veiled by a thin muslin gauze, but who, on seeing that the stranger was but a boy, threw off the veil and advanced towards him, and began to thank him in the sweetest tones he ever heard. She also told him to make the house his home whenever he liked, or whenever Selim could spare him, and after saying all that was required of her to say by her son, she vanished into her own room.

After his mother had gone, Abdullah said: “Thou seest, Kalulu, that our women have customs different from thine. Wert thou a man, thou shouldst never have seen her face? Yet thou art such a big boy now, my mother is even afraid of thee. However, whatever my mother failed to tell thee, her son says. Thou art welcome: come early or late, thou must consider all my mother or I have at thy service. These are the words of my mother and of myself.”

“Thou hast done with Kalulu for the present, Abdullah. Come thou with us to my mother,” said Selim.

“Nay, Selim; my brother Kalulu must eat in my house, and then we shall go together with thee.”

“Our noon-meal is ready. Come thou and eat with us. I want Kalulu to see my mother. Come, Abdullah, we can return and take the evening meal with thee.”

Seeing Selim was urgent, and really anxious, Abdullah, being but a boy, consented, though it was against Arab custom; but he was consoled by the reflection that the principal meal was to be eaten with him; and bidding Selim stay a moment, he went back to his mother, and informed her that they should have guests for the evening meal; then returning, he sallied out with Selim and Kalulu. Simba, Moto, and Niani were at the door waiting for them, and together they proceeded to Selim’s house.

If Kalulu was impressed with the grandeur of Abdullah’s house, he was much more so with the splendid appearance of Selim’s. The shining white marble of the courtyard, the spaciousness, cleanliness, and order that prevailed; the well-dressed slaves, that came forward assiduous to please; the broad stairs, the carved portals, and the roomy entrance-hall, took away the young chief’s breath almost with surprise. He was speechless with astonishment, and he mentally compared his own miserable clay-floored hut with this grandeur. He looked for Simba and Moto, but found they were stopping at the door; they were excluded from above, whither he was ascending, and Kalulu reflected upon this.

The ante-chamber was passed, at the door of which Selim and Abdullah left their slippers, and they advanced into a grand and spacious saloon, larger than the one at Abdullah’s house, more superbly furnished, with numbers of curious things which Sheikh Amer had collected through his Bombay agent.

Selim turned round to Kalulu and asked:

“How does the young King of Ututa like his brother Selim’s house?”

“Thou art greater than I, my brother. I have had thousands of warriors who would have done my slightest bidding; but I am the first King of Ututa who ever saw a house like this. I have had plenty of ivory, and cows, and sheep, and goats that could not be counted for number, but I never had a house like this.”

“By-and-by, Kalulu, when we are all men and strong, we shall take thee back to Ututa and see thee righted in thy own; thou having seen these things, thou wilt be able to do likewise. But thou and I have much to learn yet. We are boys, and we cannot fight Ferodia; but until we are men, rest with Abdullah and me at Zanzibar; make my house thy own. Stay here; I go to Call my mother, Amina, whom thou must like.”

“I shall like everything that thou dost like, Selim,” answered Kalulu, seating himself on the divan as he spoke.

Selim knocked at the door of his mother’s apartments, who came to the door. Her son respectfully saluted his mother’s right hand, and led her into the room; but when she saw a stranger and a black man, she drew back, and said:

“Who is this, my son; and what dost thou mean by bringing a slave into a place where none but Arabs are admitted? And I have left my veil behind. Fie, boy!”

“Nay, dear mother, this is only a boy; and he is not a slave, he is my brother,” answered Selim, smiling, as he beckoned Kalulu to advance, who looked somewhat awed at the transcendent beauty of Selim’s mother.

“Thy brother! How, hast thou two mothers? My lord, Amer, never told me he had other wives than those who live in this house. What folly is this, Selim, my son? Who is this boy?”

“Dost thou not know, mother? Canst thou not guess? Behold my brother, my Kalulu!”

“Kalulu!” echoed his mother, and immediately she recovered her smiles, and walking up to him, she poured into Kalulu’s ears all a fond mother could say to one whom she considered as her dear son’s saviour and deliverer, and she ended with saying:

“This house is at thy service. Command anything thou dost wish, and thou shalt be obeyed. I also, who am Selim’s mother—who for so long mourned him as dead—know how to be grateful. Simba, Moto, and little Niani, who shared his troubles with him, have already been rewarded with houses and gardens, and Selim is continually sounding their praises to me. But to thee, knowing as I do that thou hast suffered much, I shall be as a mother; and thou shalt be My Kalulu.”

The End.